When I did a second review in 2000 (published as part of Finn and Petrilli 2000), the number of documents had increased to 46. As in 1997, far too many were mediocre to bad. There were several general reasons for this poor quality. More often than not, a poor standards document stumbled on more than one count. But one common failing of poor standards was a poor treatment of biological evolution. Such a treatment could be badly written; or it could be confused; or error-filled, or timid, or hypocritical. It could suffer from some combination of these, or biological evolution could simply be absent. Quite often, the evolution of the earth and the universe suffered as well. With this in mind, the Fordham Foundation commissioned me to do a study focused on the treatment of evolution in K–12 science education standards, and this was published later in 2000 (Lerner 2000).

Since then, there has been a surge of public interest in accountability and evaluation in public education. And it will not be long before the No Child Left Behind Act mandates statewide testing of all students.

In response to all this activity, the Fordham Foundation commissioned a new review in 2005. By this time, the District of Columbia and every state but Iowa had published standards, and the tendency was toward longer documents. The task had become so large that it was undertaken by a six-member team of scientists, science teachers, and a philosopher of science. Each team member surveyed all the standards but concentrated on his or her specialty. Our report was published in December. Although the evaluations were based on the overall quality of the standards documents, experience dictated that we devote special attention to the treatment of evolution.

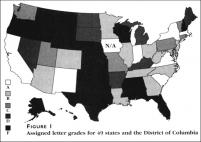

As I had done in the earlier reports, we used a set of criteria such as clarity, organization, sound content, rigor, and steady development of subject matter consistent with the maturation of the student. We assigned numerical scores for each criterion and used the total scores to assign letter grades A through F (Figure 1). There is a tendency for good standards to concentrate in the Southwest and Northeast. But that oversimplifies the fact that there are good and bad standards to be found in all regions. For example, South Carolina's and Virginia's standards were excellent, while New Hampshire's, Wisconsin's, were Oregon's were very poor.

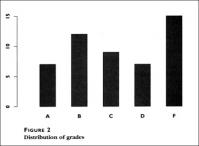

As I had done in the earlier reports, we used a set of criteria such as clarity, organization, sound content, rigor, and steady development of subject matter consistent with the maturation of the student. We assigned numerical scores for each criterion and used the total scores to assign letter grades A through F (Figure 1). There is a tendency for good standards to concentrate in the Southwest and Northeast. But that oversimplifies the fact that there are good and bad standards to be found in all regions. For example, South Carolina's and Virginia's standards were excellent, while New Hampshire's, Wisconsin's, were Oregon's were very poor.  Figure 2 shows the distribution of grades. The good news is that 19 states, where more than half of American students go to school, have excellent or good science education standards (A or B). Not so happily, 16 states scored mediocre to bad (C or D) and 15 states flunked (F). Kansas is a notorious special case to which I will turn shortly.

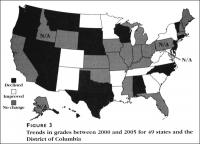

Figure 2 shows the distribution of grades. The good news is that 19 states, where more than half of American students go to school, have excellent or good science education standards (A or B). Not so happily, 16 states scored mediocre to bad (C or D) and 15 states flunked (F). Kansas is a notorious special case to which I will turn shortly. Curiously, there was a lot of churning between 2000 and 2005. Some states improved and some declined. Figure 3 shows the changes. Standards quality did not change in the states shown in white. Quality improved in the gray states, and declined in the black ones. Overall there was little change, but of the 45 states (plus the District of Columbia) that were evaluated in 2000, 12 improved, 19 declined, and 15 did not change.

Curiously, there was a lot of churning between 2000 and 2005. Some states improved and some declined. Figure 3 shows the changes. Standards quality did not change in the states shown in white. Quality improved in the gray states, and declined in the black ones. Overall there was little change, but of the 45 states (plus the District of Columbia) that were evaluated in 2000, 12 improved, 19 declined, and 15 did not change. I do not think we can take comfort in the overall steady state, given the broad attention paid to standards in recent years. Rather, it is bad news. We might expect that the availability of good state standards written in a wide variety of styles would make it easy for those states with poor standards to make improvements. Here is a situation in which the most punctilious critic will condone cribbing!

Evolution in the standards

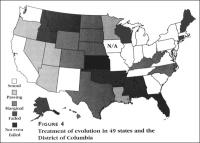

Turning specifically to the treatment of evolution, Figure 4 shows the results of our 2005 study. In this map, lighter colors represent better treatment of evolution. We lumped the As and Bs together as "sound," shown in the lightest gray (for example, California). The next darker shade of gray (for example, Arizona) stands for "passing" or C. The next darker shade (for example, Texas) represents "marginal" or D, and the blacks represent "failed" or F. Again, Kansas was a special case, rating a shameful F-minus. There is a strong — but far from complete — correlation between good quality overall and good quality in treatment of evolution. There are a few exceptions. Maine's standards, for instance, rated B in overall quality but F in its treatment of evolution. For North Carolina, we found B overall but D for evolution. In most cases, however, the difference was at most one letter grade.

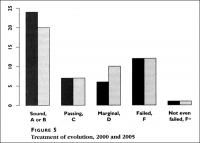

There is a strong — but far from complete — correlation between good quality overall and good quality in treatment of evolution. There are a few exceptions. Maine's standards, for instance, rated B in overall quality but F in its treatment of evolution. For North Carolina, we found B overall but D for evolution. In most cases, however, the difference was at most one letter grade. Figure 5 shows the overall results for treatment of evolution in 2000 and 2005, summed over all the states. Overall, we see pretty much the same thing as for the standards as a whole. The number of states earning A or B declined from 24 to 20; C grades held steady at 7, D grades rose from 6 to 10, and F grades remained at 12. Kansas, having fluctuated wildly in the interim between reports, retained the dubious distinction of "not even failed" — F-minus.

Figure 5 shows the overall results for treatment of evolution in 2000 and 2005, summed over all the states. Overall, we see pretty much the same thing as for the standards as a whole. The number of states earning A or B declined from 24 to 20; C grades held steady at 7, D grades rose from 6 to 10, and F grades remained at 12. Kansas, having fluctuated wildly in the interim between reports, retained the dubious distinction of "not even failed" — F-minus. It is interesting to note that, although there is a disproportionate concentration of ill-treatment of evolution in the Bible Belt, geography is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for such treatment. Georgia and South Carolina, for instance, treated evolution very well while New Hampshire and Wisconsin did not.

Just as in the general standards for science education, poor treatment of evolution in the standards can have several causes. In some cases, the issue is simply one of competence: the writers either did not or could not present evolution (or the life sciences in general) in a cogent, accurate manner. But more often, we see design at work (in more than one sense of the word!). The deliberate effort to ignore, minimize, or distort the central organizing principle of the life sciences has a long and varied history.

The standards exhibit a variety of strategies for finessing evolution: Mississippi, for example, follows a "what they don't know won't hurt them" or "ignorance is bliss" strategy. The Mississippi standards simply avoid the use of the dreaded "e-word" and present only bits and pieces of the underlying evidence. (One may draw a parallel between this approach and the ubiquitous "abstinence-only" sex education programs adopted by Mississippi, among many other states.)

Alabama, more aggressively, begins its science education standards document with the notorious "Alabama disclaimer," which singles out evolution as somehow less reliable than any other science:

The theory of evolution by natural selection, a theory included in this document, states that natural selection provides the basis for the modern scientific explanation for the diversity of living things. Since natural selection has been observed to play a role in influencing small changes in a population, it is assumed, based on the study of artifacts, that it produces large changes, even though this has not been directly observed. Because of its importance and implications, students should understand the nature of evolutionary theories. They should learn to make distinctions among the multiple meanings of evolution, to distinguish between observations and assumptions used to draw conclusions, and to wrestle with the unanswered questions and unresolved problems still faced by evolutionary theory.The Fordham report cuts to the heart of this disclaimer:

Although this is focused on evolution, and it paraphrases the "critiques" of evolutionary biology currently advanced by "intelligent design" creationism, it quite effectively derogates every branch of science. (There are, for example, many basic, "unanswered questions" about the fundamental forces of nature. Do we, for this reason, warn students to be suspicious of, or to "wrestle with," the "unresolved problems" of physics?) The Alabama preface sows confusion and offers a distorted view of what science is and how it is pursued. The quoted paragraph is preceded by mention of Copernicus, Newton, and Einstein, all physicists or astronomers; it then launches into an attack by misdirection on (evolutionary) biology. (Gross and others 2005: 27)Other school systems have mimicked Alabama, using either the language or the general approach in this disclaimer (for example, Cobb County, Georgia).

Kansas stands alone

With a history somewhere between melodramatic tragedy and low comedy, Kansas is a unique case. In 1998, when a creationist majority took control of the autonomous Kansas Board of Education, they took a workable set of science education standards and edited out all references to evolution. They went still further and deleted any subject connected to the age of the earth or the universe. This excision included such basic topics as radioactive decay (because it can be used to date objects much too old to fit a simple-minded view of the Book of Genesis) and the Big Bang (which took place long before Noah's Flood.) From this trashing of science comes the F-minus the Kansas science education standards earned in 2000.The ensuing furor led to the voting out of creationist board members in 2000 and the re-establishment of a science-friendly majority. The new board reinstated the original standards, with slight modifications. This happened soon enough that the creationist efforts had no impact on science teaching.

In the following two elections, however, a creationist majority was reestablished. The new board took a somewhat more subtle tack than their predecessors; they adopted an "intelligent design" creationist approach, but did not stop there. They formally redefined all of science to include inquiry into the supernatural. This direct attack on science as a whole is even more blatant than the indirect attack that inheres in a mistreatment of biological evolution. These grotesque distortions stand today and have earned Kansas a brand-new F-minus. Many Kansans, including the governor, the university communities, and the great majority of the science teachers, were dismayed. In the 2006 state school board elections, those in favor of keeping evolution in the standards became a 6–4 majority of the board (see http://ncseweb.org/news/2006/08/pendulum-swings-kansas-00814).

Conclusions

In conclusion, let me put science education standards in a broader context. Good standards are only one step toward quality education. It is a long way, after all, from the Department of Education in a state capital to the small rural schoolhouse in the mountains or the plains. And standards can be and have been used as a basis for writing undemanding exams, at least in language arts and mathematics. Many other matters need to be considered as well. Among these are finding and using quality textbooks, making sure teachers have adequate preparation in their subjects, and finding enough money to attract quality personnel to every aspect of public education. But if the standards are poor, it is difficult to assure quality education in all the schools of a state (an exception may be in schools in affluent neighborhoods, where well-educated parents raise well-prepared children).With respect to the teaching of evolution in particular, poor, absent, or counterfeit treatments in science education standards are practically a guarantee that evolution will vanish from state exams, textbooks, and from many classrooms as well. There are plenty of creationists, "intelligent-design" or otherwise, who are eager to make this happen. In our day, as in the days of Scopes — or Galileo, for that matter — science needs its defenders.