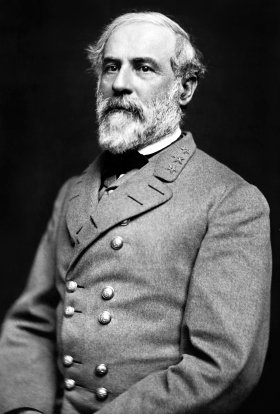

If you're a Civil War buff at all, even in a minor way, right now is not a good time to complain that you don't have any sesquicentennials to celebrate. The Battle of Gettysburg—the bloodiest encounter of the war, at least in terms of total casualties, and arguably the turning point of the war as well—was fought July 1-3, 1863. In anticipation of the anniversary, I borrowed a copy of the 1993 film Gettysburg, with Tom Berenger as James Longstreet, Jeff Daniels as Joshua Chamberlain, and Martin Sheen as Robert E. Lee. It was a little hard to find the time to watch a film running a little over four hours, but I eventually managed to do so.

There's a scene in it, set around a campfire at Longstreet's headquarters on the night of July 1, 1863, in which there's banter about Darwin. I didn't transcribe the dialogue, and I've already returned the DVDs, but Gettysburg is based on Michael Shaara's Pulitzer-Prize-winning 1974 novel The Killer Angels, which I have on hand. In the novel, Longstreet tells a visiting British officer about a previous conversation: "Well, we were talking on that. Finally agreed that Darwin was probably right. Then one fella said, with great dignity he said, 'Well, maybe you are come from an ape, and maybe I am come from an ape but General Lee, he didn't come from no ape."

In the film, as I recall it, the words are put in the mouth of George Pickett (he of the famous bloody charge), and he's expressing his own opinion, not that of a third party, but the joke is basically the same: that Lee was so revered by the soldiers and officers of the Confederate Army that they assumed that his ancestry, if nobody else's, would have to be a matter of special creation. (His reputation wasn't always so high. Early in the war, he won himself the unflattering sobriquets "Granny Lee" for losing the battle of Cheat Mountain and "King of Spades" for his extensive entrenching operations around Richmond, Virginia.)

What I wonder, though, is whether the joke is anachronistic. The Origin was published in Britain on November 24, 1859, and in the United States not much later—Appleton's in New York published the first American edition in January 1860. In the Origin, Darwin didn't address human evolution, except for a hint that "light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history"; it wasn't until the Descent of Man, published in 1871, that Darwin really addressed the subject. By that time, he was prepared to do so without compunction: "man," he asserted, "is descended from a hairy, tailed quadruped, probably arboreal in its habits."

But the fact that Darwin was cautious about addressing human evolution didn't mean that his readers couldn't put two and two together. One of the first reviews of the Origin, published in the Athenaeum on November 19, 1859, commented in its second paragraph, "Lady Constance Rawleigh, in Disraeli's brilliant tale"—the novel Tancred (1847)—"inclines to a belief that man descends from the monkeys. This pleasant idea, hinted in the 'Vestiges,'"—Robert Chambers's controversial protoevolutionary work Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published anonymously in 1844—"is wrought into something like a creed by Mr. Darwin."

Could Longstreet or Pickett have read, if not the Athenaeum's review, then at least some popular coverage of the Origin or of Darwin's ideas in general? Before the Civil War, both were serving in the U.S. Army, Longstreet in Texas and Pickett in the Pacific Northwest: were the latest periodicals making their way out west? During the Civil War, they may have been too occupied with the demands of military service—but maybe not; Lee, for one, avidly read Northern newspapers, although mainly for military and strategic purposes. What I really need to read, I guess, is a dissertation on The Popular Reception of Evolution among American Armed Forces, 1859-1865!