From Bans to “Balance”

The Supreme Court’s decision was featured in headlines around the country. John T. Scopes, whom Epperson met for lunch in 1969, told the Associated Press that the decision came “43 years too late.” By the time of the Epperson decision, the Butler Act was already a thing of the past, repealed by the Tennessee legislature in 1967. Still on the books, though, was Mississippi’s 1926 anti-evolution law. It was swiftly challenged, and in 1970, the Mississippi Supreme Court found that “in Epperson ... the Supreme Court ... has for all practical purposes already held that our anti-evolution statutes are unconstitutional.”

Of course, the affirmed unconstitutionality of evolution bans did not deter anti-evolution groups for long. In the wake of the Epperson decision, efforts to “balance” the teaching of evolution in the public schools with various supposedly scientifically credible alternatives, whether biblical creation, creation science, or “intelligent design,” became common. These efforts were challenged in the federal courts, with victories for the cause of evolution education in such cases as Daniel v. Waters (1975), McLean v. Arkansas (1982), Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), and Kitzmiller v. Dover (2005)—all citing the Epperson decision as a crucial precedent.

The View from Arkansas

As for Epperson's home state of Arkansas, the legislature has not been swayed by the pattern of losses. Anti-evolution bills have been introduced many times, even as recently as 2017. The hostility toward evolution in the state has left its mark, as it has in so many other communities in the South and around the nation. In 2009, Mark W. Bland and Randy Moore surveyed Arkansas public high school biology teachers about what they present about evolution, finding that 27 percent of teachers disagreed with the statement that teaching creationism was inappropriate, going a long way to explaining why a full 23 percent were teaching creationism in their classrooms. While headway is being made in supporting and encouraging teachers to teach evolution, public opinion on the matter has not changed as much as might be hoped in the last 30 years. Even the mere mention of the word "evolution" in science education standards continues to be a source of controversy—especially in the South.

An Agent of Change

Looking back fifty years later, I asked Epperson what she took away from it all. “Well, obviously our case did not solve the problem. As long as preachers tell their congregations that this is an anti-God idea, then there will be efforts to remove it from classes. I have learned that one cannot debate the validity of evolution with students in class. Evidence that evolution occurred is abundant, so look at the science.”

In other words, scientific evidence exists for us to follow where it leads. With students, we must define what science is and what it is not. Science is based on the evidence, not on faith; science is self-correcting, and it is not setting out to prove or disprove but rather to open our understanding through discovery.

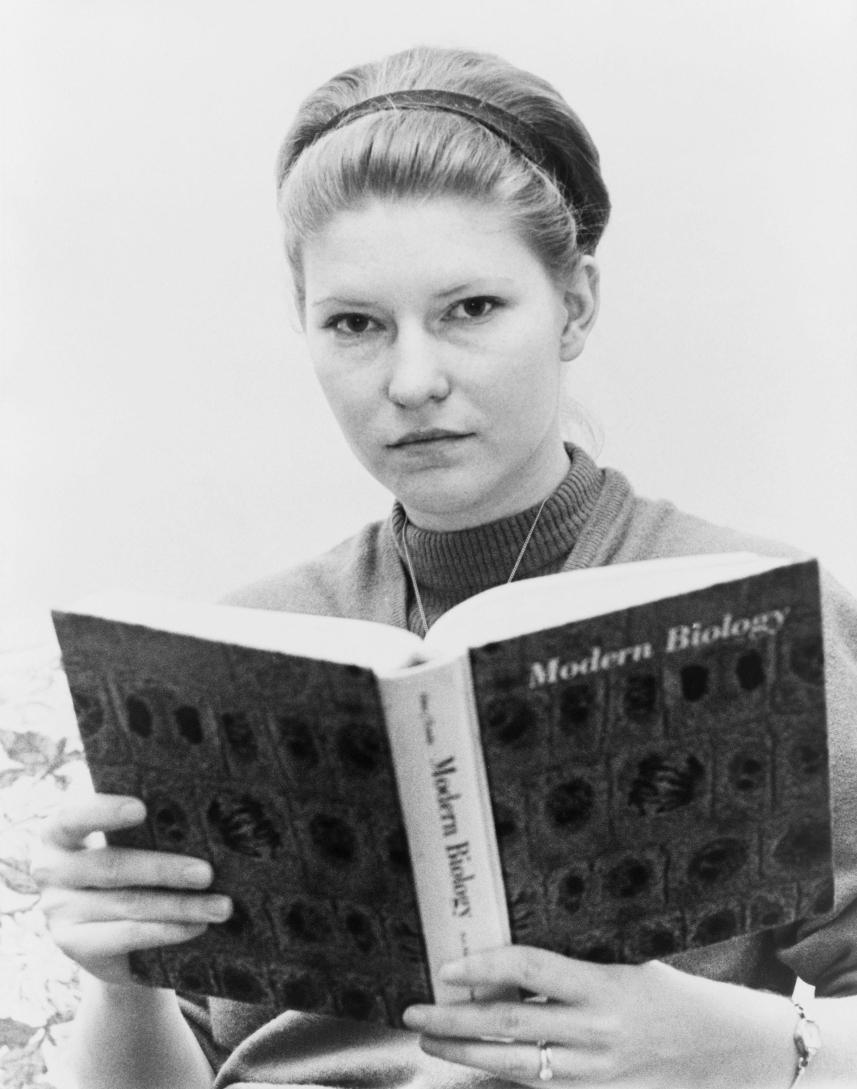

Speaking with Epperson was an amazing experience. Her willingness to stand up for what she believes, especially at a time when she had so much to lose and felt pressure to abandon her cause from many directions, should be a reminder to us all that anyone, including a young high school science teacher in Little Rock, has the potential to bring about great change.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Mark W. Bland, Randy Moore, Eugenie C. Scott, and especially Susan Epperson, for discussions and resources.