As I was researching and writing “Dixon, Not Darwin,” about a viciously racist passage sometimes misattributed to Darwin but actually taken from Thomas F. Dixon Jr.’s novel The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (1905), I was intermittently chatting with my colleague Josh Rosenau about it. Perhaps he lost the thread, because after I mentioned something about Dixon—using only his surname—Rosenau asked, “Are you talking about A. C. Dixon, the co-editor of The Fundamentals?” “No,” I replied, “I’m talking about Thomas F. Dixon Jr., the author of The Clansman.” A moment later, I added, “Golly, I wonder if they’re kin.” A quick visit to Wikipedia later, I added, “Gosh, they were brothers.” (I apologize for the strong language, but I am a man of strong passions when it comes to historical trivia.) So what’s the story?

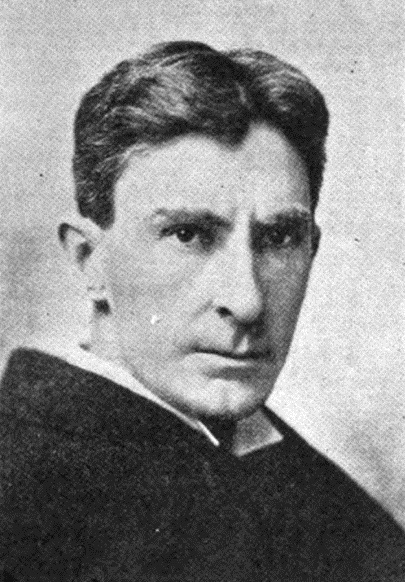

In 1848, in York County, South Carolina, Thomas Dixon, a Baptist minister, married Amanda Elvira McAfee. Their first surviving child, born in 1854, was Amzi Clarence Dixon. (Amzi? It’s a name from the Bible, in which it appears twice, in Nehemiah 11 and 1 Chronicles 6, which are basically genealogical passages.) The Dixon family migrated to central Arkansas in 1861, but returned, amid the furor of the Civil War, to the east, settling in Cleveland County, North Carolina. Thomas F. Dixon Jr. (above) was born shortly thereafter, in 1864. Both boys were educated at home and at the Shelby Academy, in Shelby, North Carolina; both then enrolled in Wake Forest College, Amzi in 1869 and Thomas following in 1879. While Amzi was in college, he felt called to preach, and was ordained in 1875, serving as a Baptist pastor in various churches in the Carolinas.

Thomas’s route to the ministry wasn’t as straightforward. At Wake Forest, he won a scholarship to attend graduate school at the Johns Hopkins University, where one of his classmates was the young Woodrow Wilson (whose attitude to evolution I mentioned in part 1 of “Searching for F. E. Dean”). In Baltimore he became stage-struck and moved to New York to act, but, unsuccessful, returned to Shelby, studied law, and was elected to the state assembly. He was admitted to the bar, but ultimately decided to follow his father and his older brother into the ministry. Ordained in 1886, he served as a Baptist pastor in various churches in the Carolinas, then in Boston, and then, after 1889, in New York. Amzi, meanwhile, after declining the presidency of Wake Forest College, moved to a church in Baltimore in 1882 and then a church in Brooklyn in 1890.

With both brothers serving as Baptist pastors in New York, it might sound as though their careers were converging. But finding his commitment to the church waning, Thomas resigned from the Baptist ministry in 1895 and stopped preaching altogether in 1899 to become a full-time lecturer and writer. He was inspired to write his historical novels extolling the antebellum South—The Leopard’s Spots (1902), The Clansman (1905), and The Traitor (1907)—after seeing a theatrical production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin that he regarded as outrageous. In all, he wrote twenty-two novels, as well as plays and screenplays; a professor of English literature describes his fiction as “the most powerful shaping factor of the southern image for twenty years or so,” succeeded by Gone with the Wind (whose author was a fan of Dixon). He died in 1946 and is buried in Shelby.

Meanwhile, Amzi stayed in the ministry but bounced around: from Brooklyn to Boston to Chicago to London to Baltimore again, where he ended his career. A sympathetic article describes (PDF) him as “[s]omething of a microcosm of fundamentalism … [who] embodied the qualities of personal piety, evangelistic zeal … and a fervent disdain for what he called the ‘vagaries of modernism.’” Those vagaries included “Roman Catholicism, liquor and licentiousness, gambling, Henry Ward Beecher’s liberalism, Robert Ingersoll’s agnosticism, Christian Science, Unitarianism, and higher criticism of the Bible.” That disdain was manifested in his involvement in the production of The Fundamentals (1910–1915); Amzi oversaw the first five of the twelve volumes (with R. A. Torrey taking over thereafter). He died in 1925 and is buried in Baltimore.

In Redeeming the South (2000), the historian Paul Harvey writes that “[Amzi] abhorred Thomas’s popular works of fiction as much as Thomas poked fun at Amzi’s stuffy theology.” It would be amusing to think so, although it’s not clear to me on what evidence Harvey bases his claim. At any rate, whatever fraternal animosity there may have been between them, the Dixon brothers at least agreed on evolution. In Living Problems in Religion and Social Science (1889), for example, Thomas was skeptical of evolution, claiming that to accept evolution is to posit no fewer than three miracles. Amzi, for his part, regarded evolution as a Trojan horse for the modernism he opposed, and his Evangelism Old and New (1891) repeatedly describes it as “the pagan theory of evolution.” But neither Dixon ever really published a full-scale assault on evolution.

I’ll end with a final irony, which Josh Rosenau (a good sport) noted. In 1955, Miriam Allen deFord published a short biographical memoir in The Humanist. Of her subject, she said that, growing up in Baltimore,

He was reared in the Baptist church and his first Sunday-school teacher was the wife of the Reverend Thomas Dixon, notorious both for his anti-Negro novels and his Fundamentalist activities; but it may be added that [he] and his two younger brothers … so plagued poor Mrs. Dixon with their critical questions and arguments that she called on their mother and asked that they be kept away from the Sunday school!

Here deFord, like Rosenau sixty years later, was confusing Thomas and Amzi. It was a confusion that she corrected in her 1956 full-scale biography of the same person—none other than Maynard Shipley, the founder of the Science League of America!