I just love it when scientists respond to criticism by rolling up their sleeves and doing science. This is especially heartening during magical thinking, er, I mean, campaign season.

What follows is a two-step story of science making an effort to get it right when facing internal doubt. In the early years of the new millennium, a couple of high-profile fraud cases rocked the field of psychology. For those who had been raising alarms about the reproducibility of scientific results for some time, the fraud cases were a clear sign that the problem went beyond simple fraud at the individual level. They argued that publishing incentives that reward novelty and discourage replication had created an environment in which fraud is more likely to go undetected, perhaps even encouraging systemic fraud.

The resulting doubts about scientific integrity were dire enough that a group of researchers was able to attract major foundation funding to carry out an experiment. Called “The Reproducibility Project: Psychology,” the researchers set out to replicate 100 psychology studies published in high-impact journals in 2008. They worked with the original authors to replicate the original conditions as closely as possible. Their sobering results were published in 2015. Just 39% of the studies could be reproduced.

Now I am not going to hold against this extremely flashy and surprising study, that has not to my knowledge been replicated, the fact that it was not published in an open access journal for anyone to read, but rather, in Science. After all, Science is one of those for-profit, high-impact journals whose editorial decisions purportedly incentivize scientists to publish results that are flashy and surprising, and at the same time disincentivize the sharing of negative results or full details of experimental methods. Kind of ironic that this particular paper was published there, but hey, that doesn’t make it wrong. The results it reports have, I gather, around a 40% chance of being replicable.

But are they correct?

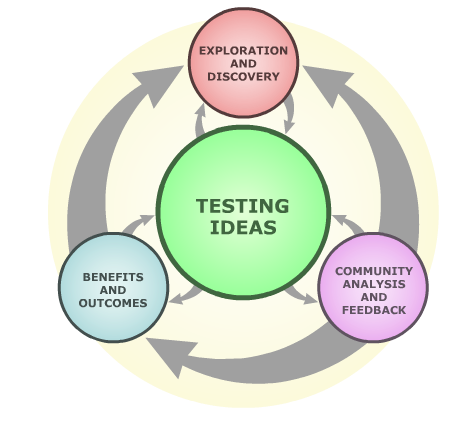

That brings us to the second part of the story. In the New York Times last weekend, Jay Van Bavel, associate professor of psychology at New York University, described an experiment he and his colleagues carried out to test a hypothesis about why so many studies failed to replicate. I think it’s pretty clever.

Remember that the results in doubt were from psychology studies. Van Bavel and colleagues noted that many psychology experiments are heavily context dependent. Van Bavel describes what he means by “contextually sensitive” as follows:

Imagine a study that examined whether an advertisement for a “color-blind work environment” was reassuring or threatening to African-Americans. We assumed it would make a difference if the study was conducted in, say, Birmingham, Ala., in the 1960s or Atlanta in the 2000s. On the other hand, a study that examined how people encoded the shapes and colors of abstract objects in their visual field would be less likely to vary if it were rerun at another place and time.

Van Bavel and his colleagues recruited a team of psychologists and asked them to rate all 100 of the studies from the Reproducibility Project based on the contextual sensitivity of the study. The results were published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. I find it neither surprising nor flashy that those studies rated most contextually sensitive were also least likely to have been successfully replicated.

Van Bavel and his colleagues recruited a team of psychologists and asked them to rate all 100 of the studies from the Reproducibility Project based on the contextual sensitivity of the study. The results were published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. I find it neither surprising nor flashy that those studies rated most contextually sensitive were also least likely to have been successfully replicated.

It’s that old “unknown unknown” problem again; biological studies—and human behavior studies in particular—are examining phenomena of such staggering complexity that there are simply too many variables to successfully control, or even name. Those studies carried out in contexts where variables were objectively rated as harder to control were also harder to reproduce.

So is there a crisis of reproducibility or not? I’m going to come to a stubbornly equivocal conclusion: yes and no. There is definitely room for improvement. Intense competition for research dollars and academic job security, unconscious bias, pressure to publish in big-name journals, and the lack of a mechanism to share negative results no doubt all contribute in one way or another to the skewing of published results toward the over-hyped and the underpowered. On the other hand, there is a wealth of evidence, of which Van Bavel et al.’s study is just one example, that failure to reproduce does not mean that results were wrong, or that deliberate fraud was involved in the research. Reproducibility problems may, instead, mean that we’re about to learn a little bit more about how the world works. I hope, as the “reproducibility” bandwagon gathers speed (the same group that carried out the project for psychology is now doing a similar study on cancer research results), its practitioners will do everything they can to root out and control for their own biases, and avoid throwing the science baby out with the replication bathwater.

Cat in a box credit: from Creative Commons: https://www.flickr.com/photos/dantekgeek/522563155