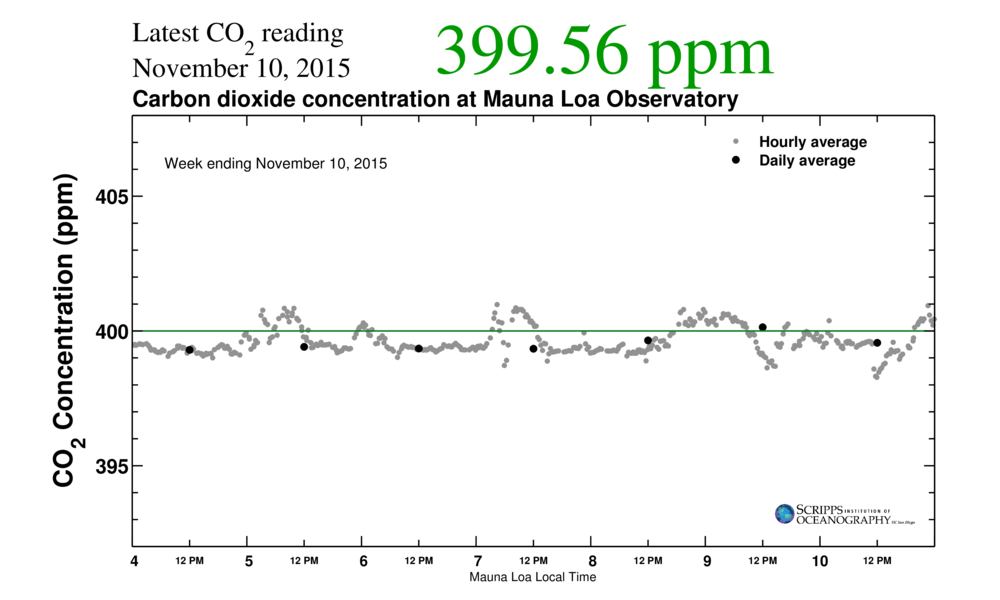

We will soon live in a world with an atmosphere permanently above 400 parts per million (ppm) CO2.

As I discussed in part 1, sometime in the next year the last sub-400 measurement will occur. In fact, measurements made last week may be the very last below 400 ppm. But even if a brief measurement in the high 300s sneaks in some time later, CO2 levels above 400 ppm will soon be here to stay for the rest of our lifetimes—and the lifetimes of our children, our grandchildren, our great-grandchildren... Let’s examine what that means.

High carbon dioxide is to the Earth what diabetes is to the individual: virtually every system is affected. The inability of the body to regulate blood sugar contributes to a host of medical problems: heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, blindness. Likewise, the inability of planet Earth to regulate the quantities of carbon dioxide we are pumping into the atmosphere affects many natural systems: glacial ice, ocean circulation, migration patterns, the timing of insect hatchings. Both diabetes and rising CO2 are examples of failed regulatory systems. In the case of diabetes, the body’s glucose regulatory system cannot cope with the blood sugar created when a person eats food for energy. In the case of CO2, Earth’s regulatory systems cannot manage the carbon dioxide created when industry burns fossils fuels for energy.

What does 400 ppm mean for us? What are the consequences? It turns out we have a very good idea. Geologists know a lot about a 400-ppm world because it’s happened before.

The Mid-Pliocene, from 3.3 to 3 million years ago (Ma), is a good analog for our current conditions. Concentrations of CO2 ranged from 360 to 400 ppm. Temperatures were 2–3oC warmer globally, but 11–16oC warmer in the Arctic (and today no place on Earth is warming as dramatically as the Arctic). The Pliocene’s Arctic Ocean was probably ice-free during summer. Sea level in this 400-ppm world was also dramatically different than today, with oceans ranging 15–25 meters higher than now, but possibly spiking up to 40 meters higher.

Forty meters. (For you Yanks who measure things oddly, that translates to over 130 of what you call “feet.”) With that much sea level rise—or even with the low range of 15 meters—it’s likely (as Emily Schoerning recently mentioned) that parts of coastal cities would be so flooded they would have to be abandoned—New York, Washington, Boston, San Francisco, Amsterdam, Hong Kong. Such a sea level rise would transform our world; swaths of entire countries, such as Bangladesh, would disappear beneath the waves. And yet this isn’t speculative science fiction—tens of meters of sea level rise happened the last time we had a 400 ppm world. We’re at this CO2 level right now.

Sometimes climate acts like the Titanic, a big ship with a tiny rudder that turns only slowly (tragically, too slowly for Jack and Rose, though science proves there was enough room on that raft). Sea level will probably rise relatively slowly, and we’re not going to see a 25 meter rise anytime in our lifetimes. But certainly by the end of this century, sea level is going to be at a minimum 1–2 meters higher; some modeling suggests this is too conservative. In fact, a recent paper by noted climate scientist James Hansen and his colleagues suggests such estimates may be far too conservative, and we may face several meters of rise in as little as 50 years (a conclusion disputed by other scientists, it should be noted).

But climate doesn’t always turn as sluggishly as the Titanic. Geologists know of many moments in Earth’s history where changes occurred at the speed of a Plymouth Road Runner driven by Vin Diesel. For example, the Younger Dryas period, from 12.9 to 11.7 thousand years ago, saw dramatic, abrupt swings in temperature. At the end of the Younger Dryas, Greenland temperatures jolted up 10oC in a decade. By way of comparison, worldwide temperatures have gone up only 0.8oC since 1880. And these wild swings of the Younger Dryas occurred long before humans began chuffing carbon into the atmosphere in such quantities that we are disturbing the naturally unstable, non-linear climate.

So what does this new 400 ppm world mean for us? It reminds me of an apocryphal Chinese curse: “May you live in interesting times.”