I was visiting Chicago, that toddling town, in late July and early August, 2015, and I was inexorably attracted to the Field Museum of Natural History—one of the world’s greatest natural history museums, according to my guidebook, as well as the permanent home of a T. rex named Sue. (Speaking of Sue, while I was in Chicago, I attended a marvelous production at the Mercury Theater of Ring of Fire: The Music of Johnny Cash, which culminated with a performance of the Shel Silverstein song “A Boy Named Sue”—which, as I have mentioned before here at the Science League of America, was supposedly inspired by Sue Hicks, a Dayton, Tennessee, attorney who helped to prosecute John T. Scopes in 1925. It is owing to such coincidences that I find it difficult to take a real vacation away from the creationism/evolution conflict.)

Anyhow, the Field Museum amply lived up to the guidebook’s description. The part that I liked the best, unsurprisingly, was the permanent Evolving Planet exhibit, which, according to the museum’s website, “takes visitors on an awe-inspiring journey through 4 billion years of life on Earth, from single-celled organisms to towering dinosaurs and our extended human family. Unique fossils, animated videos, hands-on interactive displays, and recreated sea- and landscapes help tell the compelling story of evolution—the single process that connects everything that’s ever lived on Earth.” After writing a multipart series on tree diagrams here (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4), my colleague Stephanie Keep will be particularly pleased to hear that there was a cladogram at practically every display.

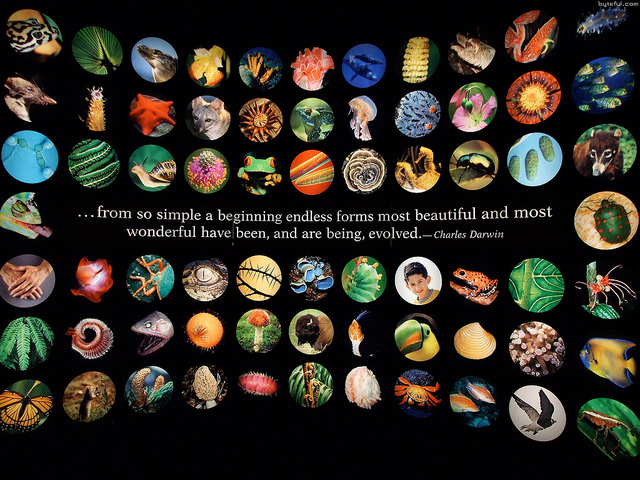

There’s a lot to like about Evolving Planet, and I won’t attempt even to inventory the high points: you simply should go visit the Field Museum in person. Thanks to a microsite, you can even see a lot of the exhibit on-line, without visiting Chicago—but you apparently can’t see the climax. At the very end of Evolving Planet, a curved alcove features perhaps a hundred backlit circles with brightly colored photographs of various organisms, amid which there appears the iconic quotation from the conclusion of On the Origin of Species: “…from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved,” correctly attributed to Charles Darwin. Correctly attributed, but also apt and moving and, at 111 characters, eminently tweetable (see, e.g., the Field Museum’s own March 5, 2015, tweet).

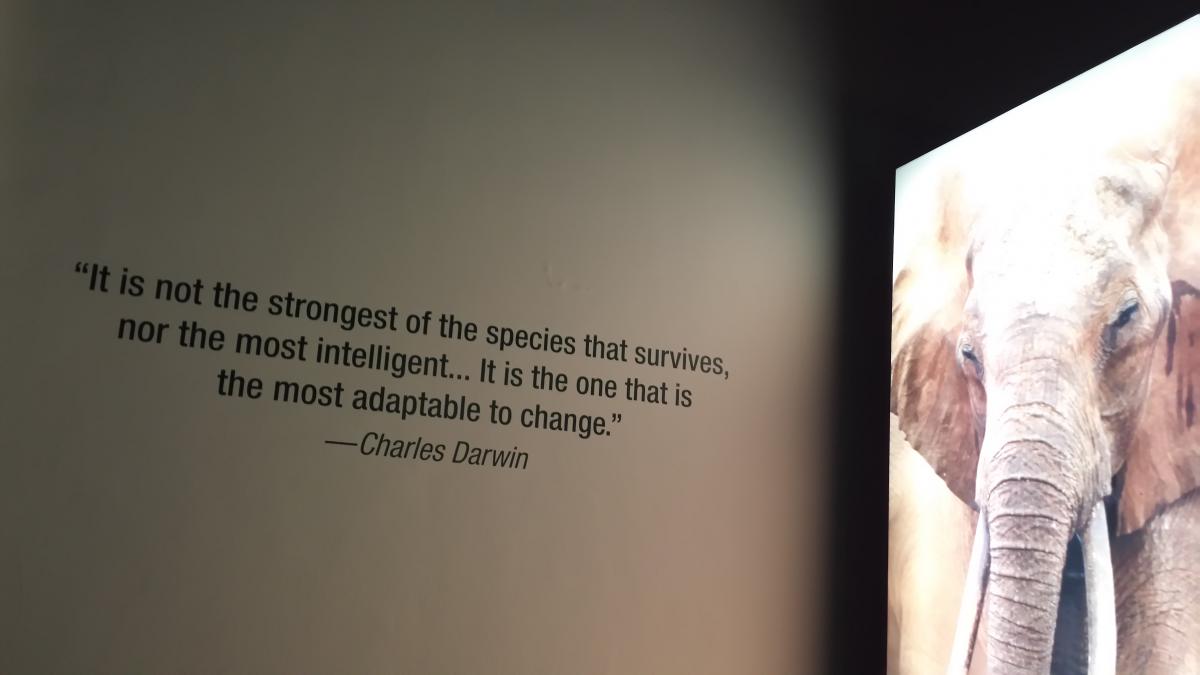

Elsewhere, though, the idea of using a quotation from Darwin to encapsulate the guiding thought behind a whole exhibit crashed and burned. A temporary exhibit called Mammoths and Mastodons reviews the evolutionary history of the Proboscidea, which—parenthetically—always makes me melancholy. Of the ten families of Proboscidea, only the Elephantidae—represented only by Asian elephants and African elephants—are alive today. And elephants aren’t doing so well themselves, thanks to us. Anyhow, at the end of Mammoths and Mastodons, there prominently appears on a wall the following quotation: “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent… It is the one that is the most adaptable to change,” attributed to Charles Darwin. Reasonably apt, reasonably moving, and at 107 characters, still tweetable—but not correctly attributed.

The “most adaptable to change” quotation was posted by the Darwin Correspondence Project in a list of “Six things Darwin never said—and one he did” a while back. In 2009, writing on The Panda’s Thumb blog, my former colleague Nick Matzke (now a research fellow at the Australian National University in Canberra) identified the actual source of the quotation: Leon C. Megginson, Professor of Management and Marketing at Louisiana State University, who offered it as a paraphrase of Darwin’s thinking first in a paper published in 1963. Matzke commented, “The quote appears to start as a paraphrase; there is no evidence that Megginson initially intended this to be taken as an exact quote; rather, at some later stage, someone copied down the phrase (perhaps in lecture notes, for example), and then later assumed it was an actual quote of Darwin.”

The “most adaptable to change” quotation was posted by the Darwin Correspondence Project in a list of “Six things Darwin never said—and one he did” a while back. In 2009, writing on The Panda’s Thumb blog, my former colleague Nick Matzke (now a research fellow at the Australian National University in Canberra) identified the actual source of the quotation: Leon C. Megginson, Professor of Management and Marketing at Louisiana State University, who offered it as a paraphrase of Darwin’s thinking first in a paper published in 1963. Matzke commented, “The quote appears to start as a paraphrase; there is no evidence that Megginson initially intended this to be taken as an exact quote; rather, at some later stage, someone copied down the phrase (perhaps in lecture notes, for example), and then later assumed it was an actual quote of Darwin.”

The Field Museum isn’t the first museum to have been megginsoned, to coin a word. On the floor of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, the “most adaptable to change” quotation appears in foot-high letters on the stone floor. It remains there, but the academy removed its misattribution to Darwin when informed of it, according to Colin Purrington. The Field Museum’s version of it appears to have simply been painted or printed on the wall, so it would presumably be considerably easier to fix, but the Mammoths and Mastodons exhibit closes on September 13, 2015, so I’m not optimistic about the museum summoning the will to fix it first. “Great is the power of steady misrepresentation,” as I think that Leon Megginson once said, “but the history of science shows how, fortunately, this power does not endure long.”