A while back, on Twitter, the wonderful anthropologist/dog-rescuer @Paleophile and I were talking about our favorite xenarthrans. Hers: sloth. Mine: pink fairy armadillo and two-toed sloth (tie). Then I said:

Can we also talk about how [X]enarthra would be the perfect clade if the pangolin was a part of it?

I recently promised Steve Bowden a sloth post, so I’m going to use this tweet as the basis.

It used to be that Xenarthra was the perfect clade—well, almost. Armadillos and sloths and anteaters and pangolins and even aardvarks used to be in the same order—not called Xenarthra, but Edentata, a term attributed to Félix Vicq d’Azyr and Georges Cuvier, both leading French biologists in the late eighteenth century. They chose Edentata, meaning “toothless,” in recognition of the fact that all members of the order had either no teeth (like anteaters and pangolins), or lacked front incisors and had poorly-defined molars (like armadillos, aardvarks, and sloths).

It used to be that Xenarthra was the perfect clade—well, almost. Armadillos and sloths and anteaters and pangolins and even aardvarks used to be in the same order—not called Xenarthra, but Edentata, a term attributed to Félix Vicq d’Azyr and Georges Cuvier, both leading French biologists in the late eighteenth century. They chose Edentata, meaning “toothless,” in recognition of the fact that all members of the order had either no teeth (like anteaters and pangolins), or lacked front incisors and had poorly-defined molars (like armadillos, aardvarks, and sloths).

Edentata was like the Beatles of Mammalia, if you ask me. But it couldn’t last. In 1872, after a big family reunion atop the Apple recording studios in London, I like to imagine, the band split up, due to Thomas Henry Huxley. Yes: when he wasn’t being Darwin’s bulldog, Huxley was Edentata’s Yoko Ono. The aardvarks, the pangolins, and the New World edentates parted ways to pursue, as they say, solo careers.

The most solo of the careers was the aardvark’s. There’s only one species of aardvark, which is in the only genus of aardvark, which is the only surviving family of their order, Tubulidentata. Their closest living relatives are thought to be sirenians (dugongs and manatees), hyraxes, and elephants. Aardvarks are awesome enough for just having a name starting with “aa” but they also can eat up to 50,000 termites in one sitting. (I really want to read the study that lead to that conclusion; don’t you? I mean, did someone have to count the termites?)

The most solo of the careers was the aardvark’s. There’s only one species of aardvark, which is in the only genus of aardvark, which is the only surviving family of their order, Tubulidentata. Their closest living relatives are thought to be sirenians (dugongs and manatees), hyraxes, and elephants. Aardvarks are awesome enough for just having a name starting with “aa” but they also can eat up to 50,000 termites in one sitting. (I really want to read the study that lead to that conclusion; don’t you? I mean, did someone have to count the termites?)

The seven or eight living species of pangolins are all placed within a single genus, in a single family, in the order Pholidota, whose closest living relatives are likely the diverse order Carnivora, which includes weasels, bears, seals and sea lions, cats, and dogs. Beloved by David Attenborough and Prince William, pangolins are suffering from too much love all around—they might just be the most heavily trafficked animal on Earth. Illegal trade for their scales (sold as a cure-all) and meat has made pangolins among the most endangered animal groups. Small comfort that their sticky ant-catching tongues attach way way back inside their bodies near the pelvis.

The seven or eight living species of pangolins are all placed within a single genus, in a single family, in the order Pholidota, whose closest living relatives are likely the diverse order Carnivora, which includes weasels, bears, seals and sea lions, cats, and dogs. Beloved by David Attenborough and Prince William, pangolins are suffering from too much love all around—they might just be the most heavily trafficked animal on Earth. Illegal trade for their scales (sold as a cure-all) and meat has made pangolins among the most endangered animal groups. Small comfort that their sticky ant-catching tongues attach way way back inside their bodies near the pelvis.

As for the New World edentates—armadillos, sloths, anteaters—they were swiftly rechristened after the breakup. When he wasn’t fighting with O. C. Marsh over who discovered which dinosaur in the American West, Edward Cope proposed a new name for the New World edentates in 1889: Xenarthra.

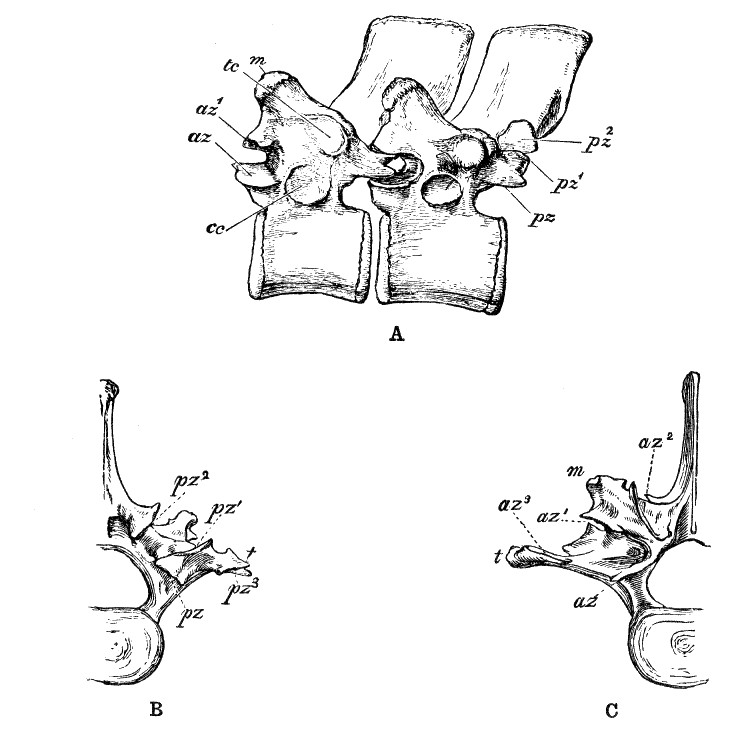

Why “Xenarthra”? It means “strange joints,” referring to the extra articulations in their vertebral joints. Of course, xenarthrans might retort that it’s all the other mammals that have strange joints! Some biologists postulate these extra places of connection along the backbone help support the back while digging, something anteaters and armadillos do very well. If this hypothesis is correct, it might help explain why this condition of xenarthy is somewhat reduced in sloths—who don’t do much of anything except hang.

Why “Xenarthra”? It means “strange joints,” referring to the extra articulations in their vertebral joints. Of course, xenarthrans might retort that it’s all the other mammals that have strange joints! Some biologists postulate these extra places of connection along the backbone help support the back while digging, something anteaters and armadillos do very well. If this hypothesis is correct, it might help explain why this condition of xenarthy is somewhat reduced in sloths—who don’t do much of anything except hang.

Speaking of Steve Bowden’s favorite xenarthrans, sloths likely have the slowest digestive rate of any mammal, taking 16 days, on average, to pass a meal. (This study I did read up on—it involved red dye. Pretty clever.) They are also the most charming animals ever. Really, I dare you to watch this video and not smile. And finally, sloths have weird necks. Almost all mammals have seven neck vertebrae, but the two-toed sloths have five to seven neck vertebrae and three-toed sloths have eight or nine. My college advisor, Emily Buchholtz, has been researching this and found a developmental mechanism behind this oddity.

Speaking of Steve Bowden’s favorite xenarthrans, sloths likely have the slowest digestive rate of any mammal, taking 16 days, on average, to pass a meal. (This study I did read up on—it involved red dye. Pretty clever.) They are also the most charming animals ever. Really, I dare you to watch this video and not smile. And finally, sloths have weird necks. Almost all mammals have seven neck vertebrae, but the two-toed sloths have five to seven neck vertebrae and three-toed sloths have eight or nine. My college advisor, Emily Buchholtz, has been researching this and found a developmental mechanism behind this oddity.

Anteaters have a following at NCSE. Whenever people are discussing purchasing skull casts—which seems to arise as a topic of conversation more than it might at the average bank or coffeehouse or department store, for some reason—there is a vocal contingent that wants a cast of the skull of the giant anteater. But for some unknown reason, deputy director Glenn Branch is afraid of, or disgusted by, or resents the silky anteater. No one knows why, and he says that he doesn’t want to talk about it.

Anteaters have a following at NCSE. Whenever people are discussing purchasing skull casts—which seems to arise as a topic of conversation more than it might at the average bank or coffeehouse or department store, for some reason—there is a vocal contingent that wants a cast of the skull of the giant anteater. But for some unknown reason, deputy director Glenn Branch is afraid of, or disgusted by, or resents the silky anteater. No one knows why, and he says that he doesn’t want to talk about it.

And let’s not forget the armadillos, the “little armored ones.” Only the Brazilian three-banded armadillo can curl into a tight ball, but they all have a tough armor that helps keep predators at bay. The nine-banded armadillo, the species that you can find in the American southwest, almost always gives birth to four identical babies that all develop from a single egg. The pink fairy armadillo is, as I say, adorable, but having seen a video of the screaming hairy armadillo doing its thing, I’m considering changing my phone's ring tone.

Extinct xenarthrans include my all-time favorite extinct animal, the massive glyptodon (seriously, look at that lower jaw! It’s amazing) as well as my daughter’s favorite, the giant ground sloth, fossils of which were famously found by Darwin

Extinct xenarthrans include my all-time favorite extinct animal, the massive glyptodon (seriously, look at that lower jaw! It’s amazing) as well as my daughter’s favorite, the giant ground sloth, fossils of which were famously found by Darwin  in South America. Its similarities to living sloths got Darwin’s brain a-whirring, to the benefit of everyone. (If he hadn’t found it, would we all talk about Wallace’s theory and not Darwin’s? Or would the finches, tortoises, flightless birds, and well, everything else have been enough?

in South America. Its similarities to living sloths got Darwin’s brain a-whirring, to the benefit of everyone. (If he hadn’t found it, would we all talk about Wallace’s theory and not Darwin’s? Or would the finches, tortoises, flightless birds, and well, everything else have been enough?

That’s not nearly enough fun facts about these amazing mammals, but it’s enough for now. In part 2, I’ll discuss what we can learn about evolution from the breakup of Edentata.

Have ideas for blog posts? Questions? Comments? email or Tweet @keeps3.