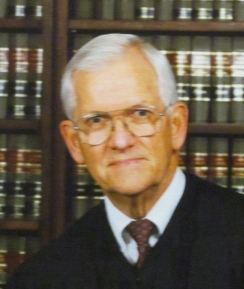

Prompted by his unlikely appearance, bragging of his youthful exploits eating oysters, in Jason Fagone’s Horsemen of the Esophagus (2006), a book on competitive eating that I happened to be reading, I’m discussing Adrian Duplantier (1929–2007), in particular his role in the legal history of the creationism/evolution conflict. (I’m not really all that interested in competitive eating, although I recommend Fagone’s book.) As explained in part 1, Duplantier was the district court judge who oversaw Aguillard et al. v. Treen et al., the case that eventually produced Edwards et al. v. Aguillard et al., the 1987 Supreme Court case that established the unconstitutionality of teaching creationism in the public schools. At issue in the case was the constitutionality of Louisiana’s Balanced Treatment for Creation-Science and Evolution-Science in Public School Instruction Act, enacted in 1981. But, as it turns out, there was a competing lawsuit, which delayed—and indeed threatened to derail—Aguillard v. Treen.

Aguillard v. Treen was filed on December 3, 1981—a day after Wendell Bird, a creationist attorney who was deputized as a special assistant attorney general to defend Louisiana’s Balanced Treatment Act, filed a legal action seeking to force the state’s educational agencies to comply with the act. Duplantier thus put the Aguillard case on hold until the prior case, Keith v. Louisiana Department of Education, was resolved. (The lead plaintiff was Bill Keith, the Louisiana state senator who was the main sponsor of the Balanced Treatment Act.) In June 1982, the court dismissed Keith on the grounds—as Edward J. Larson explains in his definitive legal history of the creationism/evolution conflict, Trial and Error (third edition, 2003)—that “because Bird’s legal action boiled down to a dispute between state officials over the implementation of a state law, the issue ‘must and should be resolved by Louisiana state courts’” (the quote is from the decision). So the ball was back in Duplantier’s court.

Duplantier’s volley was quick. On November 22, 1982, he granted a summary judgment sought by the state Board of Elementary and Secondary Education. (That was unusual in itself: the board was among the original defendants in the case, but it later switched sides!) The board contended that the Balanced Treatment Act violated, not the federal constitution, but the state constitution, which confers responsibility for curriculum and instruction to the board. Duplantier agreed, writing that the legislature violated the state constitution by “dictating to public schools not only that a subject must be taught, but also how it must be taught,” and not ruling on the Establishment Clause issues. Senator Keith and the state’s attorney general William Guste vowed to appeal. The appeal went to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which bounced it to the Louisiana Supreme Court. The Louisiana Supreme Court in turn overturned Duplantier’s decision, but remanded the case to him to consider the Establishment Clause issues.

Back in Duplantier’s court, the plaintiffs moved for summary judgment on the Establishment Clause issues, and Duplantier was amenable, granting the motion on January 10, 1985. He was visibly impatient with the prospect of a circus like the trial in McLean v. Arkansas, writing, “There is no doubt that the defendants could produce a great deal of evidence on collateral issues…We are convinced that whatever that evidence would be, it could not affect the outcome. We decline to put the people of Louisiana to the very considerable needless expense…of a protracted trial.” (Wendell Bird may have contributed to Duplantier’s impatience by submitting a 630-page brief in opposition to the motion for summary judgment. This brief would later be revised and repackaged in two volumes as The Origin of Species Revisited [1989].) With that, Duplantier’s involvement in the case ceased, although the case marched on, first to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals again and then finally to the Supreme Court.

Duplantier seems not to have discussed the case afterward—perhaps unsurprisingly, since at the time he was keen for it to vanish from his courtroom. Having now read his memoir A Louisiana Gallimaufry, posthumously published in a memorial issue of the Loyola Law Review in 2008, I regret his silence. There he discusses a lawsuit over which he presided dealing with the ownership of the Mr. Bill character from Saturday Night Live. When the time came to announce his decision, Duplantier relates, he donned a “Judge Sluggo” name tag, grabbed a giant pair of shears, and chopped up a replica Mr. Bill (sculpted from Play-Doh by his law clerk), distributing the pieces to the litigants, while a reporter cried “Oh, nooooooo!” from the rear of the courtroom. With a sense of humor like that, it would have been nice to know his candid opinion of the Balanced Treatment Act. To bring the story full circle, a chapter of the memoir details his triumph in a crawfish-eating contest. Apparently, the man never met an invertebrate on which he couldn’t binge.