In part 1 of “Inherit the Wind Avant la Lettre?” I raised a question. Noting that Inherit the Wind—Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee’s 1955 Broadway play; Stanley Kramer’s 1960 film; and the three television adaptations (1975, 1988, and 1999)—was such a hit, I asked, “[I]f the Scopes trial was so dramatic … why did it take thirty years for someone to write a play based on it?” The remainder of the post and the two following posts (part 2; part 3) were devoted to investigating the claim, to be found in The New York Times for January 2, 1927, that Majomszínház, a 1925 play by the Hungarian novelist Ferenc Herczeg (1863–1954), was the first play to be based on the trial. (The Times was interested because a translation of the play, Monkey Business, was about to begin rehearsals in New York City. Apparently it was never produced.) I concluded, “Majomszínház was not based on the Scopes trial.…But I suppose that a theatrical publicist can’t be expected to worry about the accuracy of details when a headline is in the offing!”

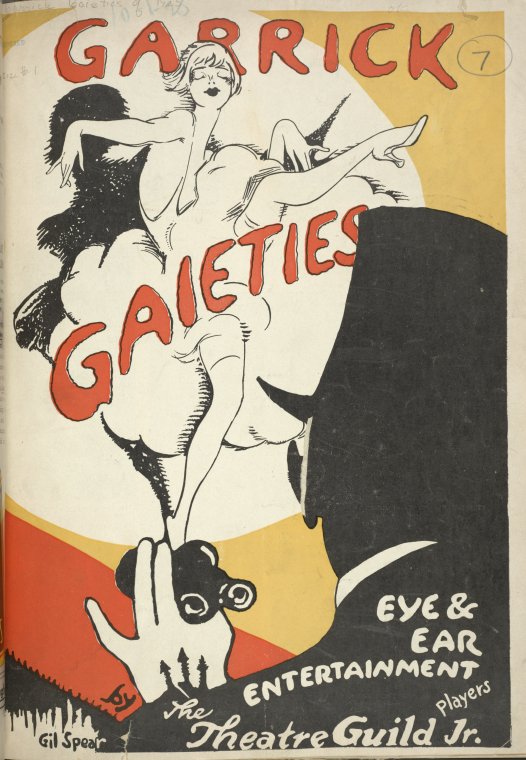

None of that, however, means that Inherit the Wind was the first theatrical treatment of the Scopes trial, although it may have been the first full-length play about the trial. And thereby hangs a tale…about “And Thereby Hangs a Tail”—a sketch based on the Scopes trial that appeared in The Garrick Gaieties, a revue that originally ran in 1925. The revue is remembered primarily as the first major production of Richard Rodgers (music) and Lorenz Hart (lyrics); its most famous song, now a standard, was “Manhattan” (“We’ll have Manhattan, / The Bronx and Staten / Island too”). The first of what were planned to be two performances was on May 17, 1925. The revue was so well received by the public and the press, though, that the run was extended on June 8, 1925, with a variety of changes. Among the changes was the insertion at the beginning of the second act of “And Thereby Hangs a Tail,” with lyrics by Hart and libretto by Morris Ryskind (1895–1985) and the revue’s director Philip Loeb (1891–1955).

The lyrics to “And Thereby Hangs a Tail” are not hard to find. They appear, for example, in The Complete Lyrics of Lorenz Hart (expanded edition, 1995). The libretto, however, was elusive. Ryskind was a prolific writer, who wrote the screenplays for The Cocoanuts (1929), Animal Crackers (1930), and A Night at the Opera (1935), all successful vehicles for the Marx Brothers; was nominated for Best Writing (Screenplay) Academy Awards for My Man Godfrey (1936) and Stage Door (1937); and won a Pulitzer Prize for drama in 1932 for the musical Of Thee I Sing (with Ira Gershwin and George S. Kaufman). But I couldn’t find the libretto in anything he published. Loeb was better known for his acting (until he was blacklisted as a supposed Communist in the 1950s, leading to his suicide). Eventually, I managed to ascertain that the original libretto was housed at the Scherer Library of Musical Theatre at Goodspeed Musicals, the staff of which courteously and efficiently provided me with a photocopy.

I am unable to reproduce the lyrics or the libretto in their entirety here, for copyright reasons, but I will give a blow-by-blow description, along with comments. The sketch takes place in a courtroom in the jungle—The Complete Lyrics specifies “an African courthouse”—and the characters are wearing monkey masks. The judge speaks, explaining that in the sensational case before him, “The defendant, Abbadaba Darwin, is charged with spreading the pernicious doctrine of evolution, which teaches that that stupid animal, man, is our grandchild.” The name “Abbadaba” is presumably intended to suggest reduplicative simian chattering, as in the 1914 song “The Aba Daba Honeymoon,” which I mentioned in the comments to “Fobbing Off Evolution” since Alabama’s governor Fob James alluded to the song while expressing his views about evolution in 1995. (Chris King provided a link to a recording at the Library of Congress.) The name “Darwin” requires no explanation, I trust!

The crowd in the courtroom, including the jury, hiss their disdain, but the judge sententiously explains that the defendant, “no matter how vicious,” is entitled to a fair trial. The judge then directs the district attorney to present the prosecution’s case. The district attorney, in turn, explains that William Jennings Bryan will present the case: he is “outside waiting for the psychological moment to enter.” The moment about to arrive, the orchestra strikes up “Tammany”—presumably the 1905 song, of which there is a recording at the Library of Congress. “Tammany” was a strange, probably lazy, choice, doubtless selected to remind the audience that Bryan was a Democrat. But Bryan’s relationship with Tammany Hall was vexed. As Michael Kazin notes in A Godly Hero (2006), “After his dalliance with Boss Croker in 1900, Bryan routinely accused Tammany Hall and other urban machines of being tools of the trusts; not surprisingly, they returned his animosity.” What happens then? You’ll have to wait for part 2.