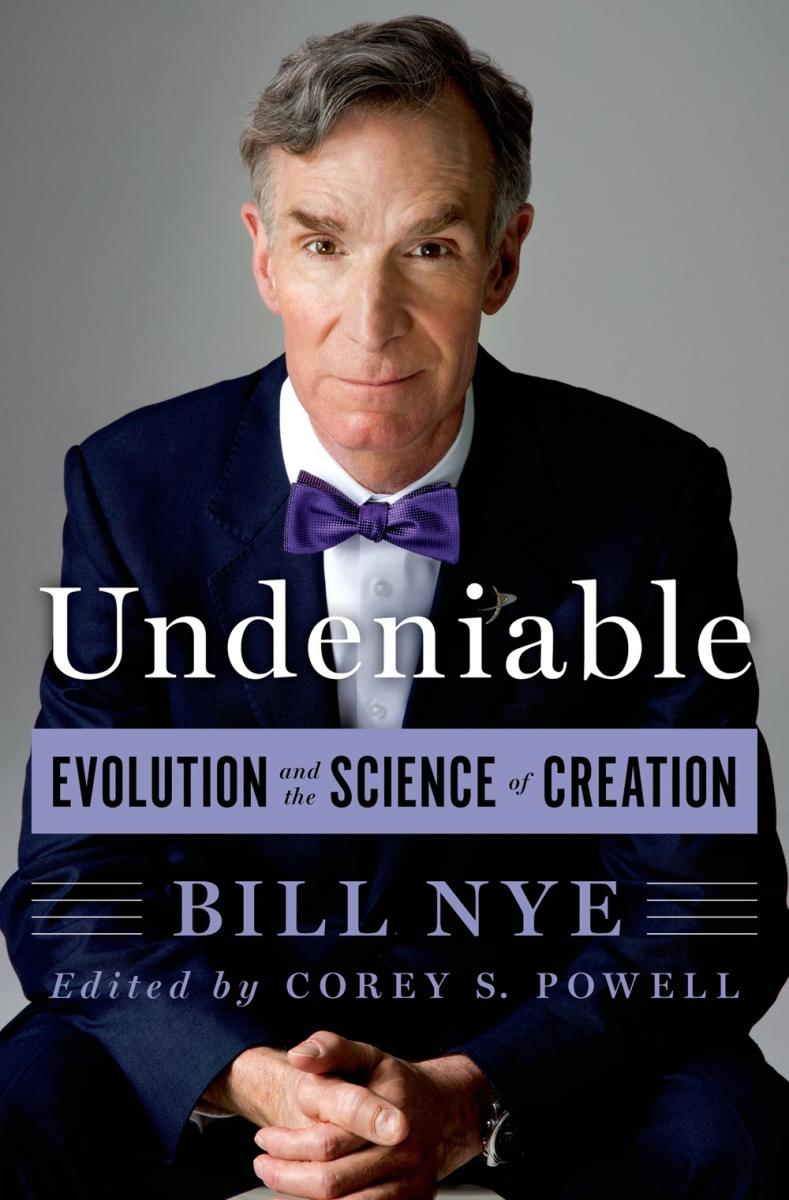

I interviewed for my post at NCSE in the wake of the Bill Nye/Ken Ham hullabaloo (which Josh Rosenau reviewed here), so watching the whole 2.5-hour-plus affair was part of my preparation. Looking back at my notes still makes me laugh, since there are all kinds of “what!?!?!”s and “this makes no sense”s. Indeed, the “debate” left me more puzzled than anything else, but I am glad I watched it, even if I’m not particularly glad that it occurred at all. The debate and its fallout continues to generate conversations, blog posts, and articles, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a book review of Bill Nye’s account of the event, Undeniable, swam within NCSE’s ken. A few people emailed the link to me, and I began reading it over a cup of afternoon coffee. At first, it seemed a pretty basic review, but toward the end, it went completely off the rails. I was left sputtering and buzzing with anger (and caffeine). A Say What? post was born.

I interviewed for my post at NCSE in the wake of the Bill Nye/Ken Ham hullabaloo (which Josh Rosenau reviewed here), so watching the whole 2.5-hour-plus affair was part of my preparation. Looking back at my notes still makes me laugh, since there are all kinds of “what!?!?!”s and “this makes no sense”s. Indeed, the “debate” left me more puzzled than anything else, but I am glad I watched it, even if I’m not particularly glad that it occurred at all. The debate and its fallout continues to generate conversations, blog posts, and articles, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a book review of Bill Nye’s account of the event, Undeniable, swam within NCSE’s ken. A few people emailed the link to me, and I began reading it over a cup of afternoon coffee. At first, it seemed a pretty basic review, but toward the end, it went completely off the rails. I was left sputtering and buzzing with anger (and caffeine). A Say What? post was born.

Let me first clarify that I am not going to comment on the book itself (I haven’t read it) or the Nye/Ham debate. I am, however, going to take the Wall Street Journal’s reviewer, science writer Nicholas Wade, to task for a complete misunderstanding of the relationship between science and religion as well as for issuing some of the worst advice to educators I have ever heard.

I’ll let Wade set the stage for us. These lines occur about two-thirds the way through:

Though most Protestant churches have followed Catholics and Jews in making their peace with Darwin, those now known as fundamentalists doubled down their bet by insisting on the Bible’s inerrancy, including even the Genesis account of the creation. Today fundamentalists oppose the teaching of evolution in schools or demand that creationism, a meretricious alternative, be given equal weight.

Mr. Nye’s fusillade of facts won’t budge them an inch. Isn’t there some more effective way of persuading fundamentalists to desist from opposing the teaching of evolution?

It was around this point that I knew things were going south. If it were possible to persuade creationists to stop opposing the teaching of evolution (as understood and accepted by the scientific community) in our public schools, wouldn’t someone have figured out how to do it by now? I was pretty sure that Wade didn’t have an idea that Genie Scott & Co. hadn’t thought of in twenty-five-plus years on the job. But just in case, let’s read on…

If the two sides were willing to negotiate, it would be easy enough to devise a treaty that each could interpret as it wished. In the case of teaching evolution in schools, scientists would concede that evolution is a theory, which indeed it is. Fundamentalists might then be willing to let their children be taught evolution, telling them it is “just a theory.”

At this point, I skipped to the author bio at the end of the piece and was completely dismayed to find that Wade is a science journalist and author with Nature and Science on his résumé. I just couldn’t believe that anyone with a stake in the scientific community would make this suggestion. Seriously? Negotiation? That’s his big idea? Concede that evolution is a theory? There is so much wrong here… First of all, whether to give our children a proper science education in public schools is not something that we should be prepared to negotiate. And it would be hard to think of a way to better undermine the integrity of science education than by advocating that we tell children and their families that evolution is “just a theory.” To do so misrepresents both the scientific standing of evolution and the meaning of the term “theory” in science.

At this point, I skipped to the author bio at the end of the piece and was completely dismayed to find that Wade is a science journalist and author with Nature and Science on his résumé. I just couldn’t believe that anyone with a stake in the scientific community would make this suggestion. Seriously? Negotiation? That’s his big idea? Concede that evolution is a theory? There is so much wrong here… First of all, whether to give our children a proper science education in public schools is not something that we should be prepared to negotiate. And it would be hard to think of a way to better undermine the integrity of science education than by advocating that we tell children and their families that evolution is “just a theory.” To do so misrepresents both the scientific standing of evolution and the meaning of the term “theory” in science.

In short: this is among the stupidest ideas about science education I have ever heard, and I have heard a lot of really bad ideas.

Wade tries to recover:

Evolution, of course, is no casual surmise but a theory in the solemn scientific sense, a grand explanatory system that accounts for a vast range of phenomena and is in turn supported by them. Like all scientific theories, however, it is not an absolute, final truth because theories are always subject to change and emendation.

Okay, he understands what it means to be a scientific theory after all. But then why does he recommend undermining it? Why resort to a kind of deception, telling the creationists that evolution is “just a theory” out of one side of the mouth and singing its praises as a grand unifying explanation out of the other? Does Wade think that this is ethical? We don’t know. But does he actually think it would work? Apparently, he does:

In their battle with fundamentalists, scientists hate to admit to even a smidgen of uncertainty. But a useful distinction can be made between evolution as a historical process, which is undeniable, and evolution as a scientific theory. The theory is not inscribed unalterably on stone tablets but is still very much a work in progress. At present, for instance, there is an intense debate—started by Darwin to explain the emergence of altruism—over whether natural selection works on groups as well as on individuals. So which version of the theory is “undeniable,” the one with group-level selection or the one without it? If popularizers like Mr. Nye could allow that the theory of evolution is a theory, not an absolute truth or dogma, they might stand a better chance of getting the fundamentalists out of the science classroom.

This is just ridiculous. First of all, scientists, and “popularizers like Mr. Nye,” do not claim to possess absolute truth or require adherence to a dogma when it comes to how evolution (or any aspect of science, for that matter) works. But that doesn’t mean that they’re less than confident about evolution. It means only that challenges to scientific conclusions have to be based on evidence, not on faith. (If Wade is reacting to the title of Nye’s book, he might have overlooked the pun in Undeniable/UndeNyeable.)

Second, it isn’t at all clear what Wade would have biology teachers do differently when he urges that they teach evolutionary mechanisms and patterns as “scientific theories” and “works in progress.” In my experience, biology textbooks and the teachers who use them already present evolutionary mechanisms and patterns as based on, and in principle responsive to changes in, the evidence. Far from presenting “undeniable” facts “inscribed on stone tablets,” educational material on evolution almost always has a focus on how various fields, such as genetics, anatomy, paleontology, and development, lend support to our working knowledge of how evolution works.

But more importantly, suggesting “evolution is just a theory,” nudge nudge wink wink, wouldn’t even work! The main problem creationists have with evolution isn’t in details such as altruism or group selection (although they will happily point to similar legitimate scientific debates over evolutionary mechanisms and patterns to claim that evolution is a “theory in crisis”). The main problem that they have is with the very core of evolution, common descent—what Wade refers to as the undeniable “historical process.” “I’m no kin to the monkey,” as the creationist ditty runs.

Many creationists won’t be happy until we say that common descent is just one idea in a range of ideas out there, including their interpretation of the Bible, to explain the history of life on Earth—and that it’s “only fair” to present all the possibilities in science class. Thankfully, both the Constitution and the courts have declared that terrible idea a non-option. But creationist assaults on the teaching of evolution continue nevertheless.

The answer to the challenge posed by these assaults is not to try to exploit the divergence between the scientific and the vernacular uses of “theory” in a transparently disingenuous and blatantly equivocating way. The answer is to help teachers work effectively with parents, students, and communities who fear that scientists are out to undermine their faith. With that fear assuaged, teachers can focus on what they should be doing in science class: engaging students, correcting and avoiding misconceptions, and inspiring future scientists and consumers of science. What teachers shouldn’t do, of course, is take careless advice from pundits who haven't thought it through. As the Scottish proverb says, “If ye dinna see the bottom, dinna wade.”