"When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." —John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra

"When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." —John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra

Over the holidays, I visited Yosemite with my wife and stepdaughter, spending a rainy night at the Lodge by the Falls on Christmas eve. Christmas Day was bright and brisk and we hiked to the base of Yosemite Falls and Mirror Lake. It was the first time they had been to the famous National Park.

Strictly speaking, it was my second visit to the park. My first visit was when I was 18 months old, so my memory of it is limited to photos from the family scrap book and stories of bears ransacking the cooler at night, opening jars of peanut butter and licking them clean.

On Christmas eve, after a less than stellar meal at the famous Ahwahnee Hotel, we retreated to our snug beds at the Lodge and watched the segment on Yosemite’s history from the Ken Burns’ PBS series on National Parks, learning about the Park’s history and in particular John Muir’s vital role as protector and advocate for national parks in general and Yosemite in particular.

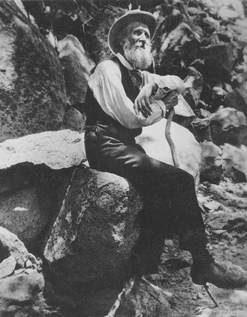

Muir, it turns out, died on Christmas eve, exactly 100 years ago, in Los Angeles.

I knew bits and pieces of lore about Muir—how he helped form the Sierra Club to support Yosemite becoming a National Park, his adventures with a dog named Stickeen surviving an ill-planned hike across a crevasse filled glacier in Alaska, and his famous quote about everything being hitched to everything else in the Universe.

What I didn’t know was that in 1903 he spent three days camping with President Theodore Roosevelt, who had asked Muir to accompany him on his visit to Yosemite. The two men walked and talked, riding by horse through the valley and around the park, having long conversations about the importance of conserving natural resources and national treasures. Muir emphasized the long-term value of federal protection of special places to inspire and nourish the people. The US National Parks, of which Muir and Roosevelt are the forefathers, are indeed true treasures, with over 280 million people visiting them in 2012.

Muir wasn’t a scientist in the professional sense of the word—he was an old school naturalist who admired the likes of Darwin, Huxley, and Tyndall. The University of California’s Calisphere website, which has collected Muir’s letters, writes:

"John Muir lived a remarkable life of science and wonder. Born in Scotland in 1838, Muir immigrated to the United States with his family in 1849 and eventually moved to northern California. There, Muir made important contributions to the science of glaciology, wrote striking and influential articles and books about the beauty of nature, and advocated for the preservation of wilderness."

Muir enjoyed making observations of the natural world and contemplating how exactly things were hitched to each other. He wrote over a dozen books, including A Thousand-mile Walk to the Gulf about his initial “botanical journey” from Indiana to Florida in 1867, published in 1913; and hundreds of articles, including one published in the October 8th, 1872 issue of Harper’s entitled "Living Glaciers of California".

Terry Gifford, author of Reconnecting with John Muir, suggests that despite his passion and evident talent for scientific observation, Muir had “a mistrust of professional scientists. In his determined amateurism and refusal to limit himself to the discourse of the professionals, Muir reached a wider audience with greater effect, gaining for himself a place not only in scientific, but also in literary history.”

Unabashed in his awe of “God’s big show,” Muir’s writing often blurs the mystic and scientific. Gifford writes: “some of Muir’s writing can seem excruciatingly New Age to the contemporary reader unsympathetic to this discourse.”

Like many scientists, Muir recognized and expressed in poetic terms that everything is connected to everything. Professional scientists must be scrupulously careful to separate their personal opinions from their scientific results, which can make it difficult for them to express the awe and appreciation of nature that often motivates their research.

All the more reason to be thankful for passionate communicators like John Muir, whose insights and devotion played so critical a role in conserving America's wilds and wilderness for future generations. One hundred years after his death, his passion continues to inspire.