BioLogos, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting evolution within evangelical circles, recently released a large survey examining how and why people develop their views on evolution. There’s a lot to mine there, though you can read the highlights in NCSE’s news item. I’m especially fascinated by the survey’s work to separate out different stances in the public conversation on how evolution and religion intersect. I’ll dive into it in a bit, but I want to touch on some of the surrounding media coverage first.

Archaeopteryx by Melissa Frankford.

Archaeopteryx by Melissa Frankford.I heard about the study about two weeks before it was released, when The Atlantic’s Emma Green called to ask some questions. We talked about one of the study’s major themes, what drives people’s beliefs around evolution and religion (I hadn’t yet seen the study, but I think what I said actually aligns nicely with the findings). I explained why efforts to simply use science evidence to confront creationist misperceptions can go awry:

“No creationist wakes up in the morning and says, ‘I have really strong opinions about whether Archaeopteryx is the ancestor of modern birds,’” [Rosenau] said. “Who are we as people? That’s the question that they think evolution is answering. What does it mean to be a person? What does it mean to be an animal?”

In other words, the cliche of pitting science against religion is a category error, to a certain extent: Evolutionary biology provides certain insights into the mechanisms of how human life has formed and changed over time, but it can’t provide insight into the meaning behind those changes. Yet the meaning part is often what matters in vitriolic “debates” about the origins of life.

Evolutionary biologist Jerry Coyne objected to that passage, incorrectly summarizing it as:

By all means let the Little People have their religiously-inspired “meaning”—the fictions and lies that have the unfortunate side effect of polarizing humanity, killing people, disenfranch[iz]ing religious minorities, gays and women, opposing abortion and assisted dying, and terrorizing children with thoughts of hell. That is the “meaning part” that is so important for people like Rosenau (and BioLogos) to preserve.

Obviously, the “meaning” I mentioned is not the litany of evils he recites and attributes to religion at large. Indeed, my interest in the problem of creationism is rooted as much as anything in a desire to address those harmful effects of religious authoritarianism.

But opposing religious authoritarianism does not have to entail opposing religion. One of my regular beefs with these sorts of discussions is an unfortunate habit some have of talking about “religion” as if that was some unitary monolith. But it isn’t. Religion means a million things, and different people use it different ways. Some use it in dangerous, harmful ways, others use it productively. I’m sure that when Ken Ham tries to build a Noah’s Ark theme park, he thinks he is representing his faith in action. Then again, I think the image below, from a protest against police violence in Ferguson, Missouri in August, speaks to a very different idea of what faith does, and how it gives people meaning.

“I am faith in action” at clergy protest in Clayton, Mo. #Ferguson pic.twitter.com/HVR5zFbZSe

— Ben Kesling (@bkesling) August 21, 2014 Empirically, we can see that what sort of faith people have matters a lot. Pew’s Religious Landscape Survey reveals wide divergence in different religions’ and denominations’ attitudes toward evolution. Jews, Catholics, Orthodox Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, and other religious groups generally accept the science, and even mainline Protestants are basically 50-50. Pew’s data shows that it isn’t “religion” writ large, but affiliation with conservative theology and especially evangelical Protestant affiliation, that drives rejection of evolution.

I say “affiliation” quite intentionally. My point with that Archaeopteryx quote is that people don’t reject evolution based on their scientific understanding, but based on something far more complex. They wake up and say, “people like me, whom I trust and love and want to trust and love me, say that evolution is weakening our nation’s moral fiber and leading others away from being people like me. To be the sort of person I want to be, and to be a beloved member of my community, I’m going to jump on the bandwagon of evolution-bashing.” Their antievolutionism is about affiliation and community dynamics more than theology or the particulars of the rank and file’s theistic beliefs.

That’s also what the survey from BioLogos showed. Jonathan Hill, who conducted the survey, explains at the BioLogos blog:

we can identify the most dominant “recipes” for identifying as a convinced creationist…The two factors that are part of every [such] pathway are beliefs about the Bible and belonging to a religious congregation that has a settled position rejecting human evolution. In fact, just these two factors together will produce [or at least predict—JR] a convinced creationist 81 percent of the time (compared to only 38 percent of the time if someone has the same Bible beliefs but attends a congregation that has no firm position on human evolution). The social pressure from the congregation appears in four out of the five recipes, and having family that believes the same thing about origins is in three out of the five. This goes to show that intersection of certain beliefs with certain contexts is the only sure-fire way to lead to a certain creationist position.

Affiliation doesn’t just mean holding certain beliefs, it entails a personal connection (etymologically, it meant “adoption as a son”). As America’s Big Sort unfolds, people who belong to the same denomination tend to associate only with others of the same denomination, or who share the same beliefs. Regardless of the pro-evolution scientific consensus, if the consensus in that group is anti-evolution, that will be what dominates each person’s experience, and thus their beliefs.

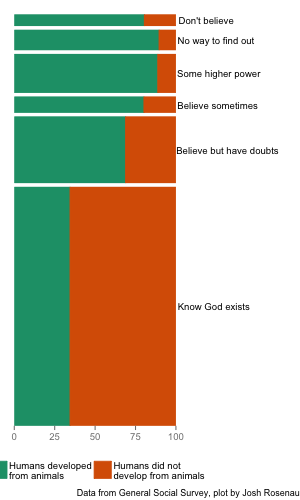

Coyne claims that the evidence indicates that theistic belief “immunizes” people against accepting evolution. Here again, Pew’s data tend to indicate otherwise: 3 in 5 Catholics accept evolution, which is hardly what you’d expect from a group “immunized” against that idea. We see a similar pattern in data from the massive General Social Survey. In the GSS samples, about 60% say they “know God exists,” with the remainder selecting either that they “don’t believe,” “there’s no way to find out,” “believe in some higher power,” “believe in God sometimes,” or “believe in God but have doubts.” While acceptance of evolution certainly declines with intensity of theistic belief, 2 in 5 who are certain God exists also accept evolution. That’s a pretty crummy rate for a vaccination.

Coyne claims that the evidence indicates that theistic belief “immunizes” people against accepting evolution. Here again, Pew’s data tend to indicate otherwise: 3 in 5 Catholics accept evolution, which is hardly what you’d expect from a group “immunized” against that idea. We see a similar pattern in data from the massive General Social Survey. In the GSS samples, about 60% say they “know God exists,” with the remainder selecting either that they “don’t believe,” “there’s no way to find out,” “believe in some higher power,” “believe in God sometimes,” or “believe in God but have doubts.” While acceptance of evolution certainly declines with intensity of theistic belief, 2 in 5 who are certain God exists also accept evolution. That’s a pretty crummy rate for a vaccination.

So religion is not a monolith, with different sorts of religion having different relationships with evolution, and the influence of religion is mediated by social context. This suggests a strategy for defeating creationism by engaging religious communities and helping them become more accepting of evolution, of offering them new ways to see evolution that those communities can accept. Coyne’s approach, arguing that religion as such is inconsistent with accepting evolution, requires setting himself and evolution at odds with all religion.

Contrary to Coyne’s claim, there’s a lot of research that indicates that the approach I’m advocating does work better at increasing knowledge and acceptance of evolution (and, mutatis mutandis, climate change, vaccines, and other instances of science denial) than trying to change a fundamental part of someone’s identity just to get the science across. There are plenty of people out there who can and do hold onto their faith and accept evolution, and I’d rather help others follow that path than deepen the unnecessary and harmful wedge between science and religion.

In the end, the dispute Coyne and I have on this point goes back to the birth of evolution. When Edward Aveling wrote a book advocating for atheism, he wrote to Charles Darwin, asking the great man's permission to dedicate the volume to him. Darwin demurred, noting that his advanced years made it hard to read through manuscripts, and he would fear that a dedication might imply his endorsement for arguments he hadn’t read.

He added perhaps the simplest summary of my own stance ever penned:

though I am a strong advocate for free thought on all subjects, yet it appears to me (whether rightly or wrongly) that direct arguments against christianity & theism produce hardly any effect on the public; & freedom of thought is best promoted by the gradual illumination of men’s minds, which follows from the advance of science. It has, therefore, been always my object to avoid writing on religion, & I have confined myself to science.

Given a forced choice between evolution and religion, I know which people will choose. I care about science literacy, so I want to help people find ways to accept the science, and as someone opposed to religious authoritarianism, I want to do that in a way that doesn’t impose my own religious views on others. So I stick to advocating for science, not against religion.