In various posts here, I’ve mentioned Luther Tracy Townsend’s Collapse of Evolution (1905), which, as Ronald L. Numbers notes in The Creationists (1992), “assembled one of the earliest—and most frequently cribbed—lists in order to prove that ‘the most thorough scholars, the world’s ablest philosophers and scientists, with few exceptions, are not supporters, but assailants of evolution.’” It wasn’t until I was eating lunch yesterday, though, that I actually read the book—as reprinted in Antievolutionism Before World War I (1995), edited by Numbers—cover to cover. There weren’t a lot of surprises in it, but I was interested to note, toward the conclusion, the claim that “every leading naturalist is echoing the words of…St. George Mivart: ‘I cannot call it [Darwin’s theory] anything but a puerile hypothesis”.

“Puerile” is a striking adjective, certainly, but what does it mean here? It would be natural to take it in the derogatory sense identified as usual by the Oxford English Dictionary: “Of conversation, thought, humour, etc.: befitting children rather than adults; childish, infantile, immature; unsophisticated; silly.” Townsend wastes no time explaining its meaning, instead continuing, “And yet even this dirge is far from being the saddest feature of Mr. Darwin’s funeral …” He wasn’t the only antievolutionist or anti-Darwinist writer to brandish Mivart’s adjective. William Bell Riley (whom I discussed in “Riled about Haeckel”), for example, improved both Mivart’s concision and his social status by referring to “Sir George Mivart’s declaration, ‘Evolution is a puerile hypothesis’” in his Inspiration or Evolution (1926). But were they accurately representing him?

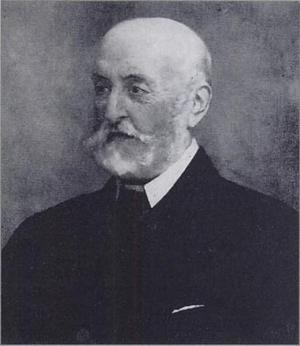

Well, who was it who described Darwin’s theory as puerile? His name in full was St. George Jackson Mivart (1827–1900)—his first name was St. George, which often seems to confuse people. A lawyer by training but a zoologist by profession, Mivart had a respectable scientific career, serving as vice president of the Zoological Society and the Linnean Society in various years, and being elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1867. Once a friend of Thomas Henry Huxley’s, he was originally enthusiastic about evolution by natural selection, but later reversed himself, particularly in On the Genesis of Species (1871); Darwin added a new chapter to the sixth edition of the Origin in part to rebut Mivart’s critique. Owing to the perception of his criticisms of Darwin as unfair, he eventually became persona non grata in Darwin’s circles.

Part of Mivart’s resistance to natural selection is attributable to his religious views. Born to evangelical parents, he became a Catholic in 1845. From about 1870 onward, Mivart accepted evolution but not natural selection, and a lot of his later writings were devoted to reconciling his scientific views with his faith. It’s sometimes claimed that he was excommunicated: not so, although some of his writings were put on the Catholic Church’s Index of Prohibited Books, and in 1900 he was forbidden to take the sacraments—on account of his views of hell, not because of his views on evolution. (For the gory details, see chapter 7 of Mariano Artigas, Thomas F. Glick, and Rafael A. Martínez’s Negotiating Darwin [2006], which corrects a number of mistakes to be found in the standard references on Mivart.)

Anyhow, the description of Darwin’s conception as “puerile” is to be found in Mivart’s Lessons from Nature: As Manifested in Mind and Matter (1876), in a chapter on natural selection. In the final paragraph of the chapter, Mivart writes:

Continued reflection, and five years’ further pondering over the problem of specific origin, have more and more convinced me that the conception that the origin of all species, “man included,” is due simply to conditions which are (to use Mr. Darwin’s own words) “strictly accidental,” is a conception utterly irrational. This conception is not that of Mr. Wallace, who makes of man a special exception. With regard to the conception as now put forward by Mr. Darwin, however, I cannot truly characterize it but by an epithet which I employ only with much reluctance. I weight my words, and have present to my mind the many distinguished naturalists who have accepted the notion, and yet I cannot hesitate to call it a “puerile hypothesis.” (emphasis in original)

He then explains:

I call it puerile and not infantine, because in the infancy of nations as of individuals the tendency is to explain each visible action by a direct supernatural intervention. Reaction from this infantine condition tends to the exclusion from our conception of the First Cause, of knowledge, purpose and will altogether, as in the Ionian Philosophy which reappears amongst us to-day—the puerile view. This puerile view results from a want of appreciation of human reason. Maturity reconciles the apparently diverging truths contained in each assertion and represents the material universe as always and everywhere sustained and directed by an infinite Cause, for which to us the word MIND is the least inadequate and misleading of symbols. (emphasis in original)

(The reference to “the Ionian Philosophy” is presumably attributing to Darwin the views of pre-Socratic philosophers who explained natural phenomena with reference to natural forces rather than with reference to the will of the gods.)

Three things are evident, then, when the paragraph from Mivart describing Darwin’s conception of natural selection as “puerile” is considered in its entirety. First, it’s fair, on the strength of the passage, to cite Mivart as a critic of Darwin’s: had Townsend and Riley confined themselves to doing so, there would be no cause to complain. But, second, despite what Townsend implies and Riley states, Mivart wasn’t criticizing Darwin’s view on evolution, only his views on natural selection. Third, and most important, Mivart isn’t using “puerile” in the derogatory sense of “silly”; he’s using it in the course of a developmental metaphor, from infancy to adolescence to maturity. Quoting Mivart’s description of Darwin’s conception of natural selection without explaining the organizing metaphor distorts its meaning and is itself—dare I say it?—puerile.