A creationist group is organizing an event at a major university (unnamed, since I certainly don’t want to promote the event), and some scientists there wanted advice on how to respond. One approach we discussed was using humor to push back. I love the idea, but it's not as simple as you'd think. How can satire and humor work? And how can they backfire? Read on.

Humor can be a really effective tool. When creationists or other science deniers are hosting an event for the sole purpose of drawing attention, you want to address the claims without turning it into a debate or lending credence to their long-debunked views or otherwise promoting the event itself. Humor lets you engage with the audience and undecided passers-by and take the deniers down a peg, all hopefully without turning anyone off from your own message or making the creationist event seem appealing.

Humor can be a really effective tool. When creationists or other science deniers are hosting an event for the sole purpose of drawing attention, you want to address the claims without turning it into a debate or lending credence to their long-debunked views or otherwise promoting the event itself. Humor lets you engage with the audience and undecided passers-by and take the deniers down a peg, all hopefully without turning anyone off from your own message or making the creationist event seem appealing.

NCSE used humor effectively in responding to a "special" edition of the Origin of Species produced by creationist Ray Comfort some years back, which he and his followers handed out on college campuses. Via a website somewhat wackier than our usual staid pages, we confronted his attacks on evolution in the book’s special introduction, and poked fun at Comfort’s infamous obsession with bananas. We made a silly video and fliers for people to hand out, and special bookmarks people could use in their new copy of the Origin, to separate the science from the bananas. It worked well at giving people something to do without giving Comfort or his people any credibility, and it let anyone in the audience around the book distribution join in the joke, rather than feeling like the butt of a joke. Done right, this kind of comic response can be devastating, and is basically impossible for the target to counter without looking whiny, humorless, small, and unworthy of attention. ComicCon counterprotests against the Phelps clan are brilliant examples of humor used to marginalize the marginal while drawing everyone else into the joke. But there are some risks, both practical and philosophical, to using humor.

The first problem is that being funny isn’t always easy, and trying to be funny and failing just makes you look bad and the other side look good. While it’s really hard to respond to a good satirical attack, it’s really easy to hit back at a failed joke. You want people laughing with you, not at you. If you aren’t funny, or your sense of humor doesn’t extend beyond fart jokes, then the joke is likely to be on you.

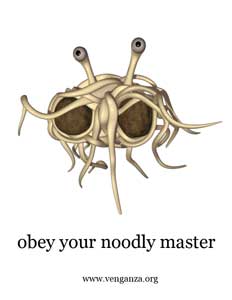

It's tricky making fun of an event without seeming to make fun of the people attending, or to mock an idea without seeming to mock those who hold it. Sometimes you might not care about reaching the folks who signed up to attend such an event, but often the aim is indeed to get them to take a more skeptical approach the nonsense being peddled. Done right, such a response draws attendees into conversation and engages people who aren’t attending but aren’t unsympathetic to the event’s big idea. Being made the butt of a joke (or having your beliefs made the butt of a joke) makes people defensive and angry and far less likely to engage. Sometimes that’s OK, as when protesting the Phelps clan. In the case of the Comfort Origin, we were careful to mock Comfort for being a silly man while praising anyone who wanted a free copy of the Origin, which separated the audience from the target of mockery, and gave a chance to talk to them about why the Origin and evolution are awesome, unlike Comfort. The Flying Spaghetti Monster (which I love as a general matter) is an example of a funny gag that can nonetheless be off-putting to some folks in the undecided middle, and has to be used carefully.

A related philosophical point: humor should punch up. It’s a tool of the powerless to use against the powerful. When humor punches down, it’s mean-spirited and likely to rebound badly; think of Rush Limbaugh’s joke of calling a law student a “slut” (Limbaugh lost tons of advertisers, while Sandra Fluke was invited to address the next Democratic national convention). Precisely because humor is so powerful, and so hard to respond to, it’s unfair (and less funny) to deploy it against people who have no resources with which to defend themselves.

Sorting out these sorts of power dynamics while dealing with creationism can be tricky. In society at large, conservative Christianity has way more influence than science. But certainly on campus, and in certain aspects of U.S. culture, science is a powerful force, and is seen in particular as an elite force. Indeed, that’s much of what drives the 90-plus-year history of this battle in American politics: a desire by conservative Christians to reclaim cultural and moral authority that they fear was lost to science. Creationism is born out of real, important, and meaningful concerns, and mocking or reinforcing those concerns will surely make it harder to draw in and engage creationists or others who sympathize with those concerns. Using humor to go after creationist events requires an angle that doesn’t look like it’s mocking people who are poor and uneducated and lack the clout and respect of scientists, and that does mock the dangerously powerful aspects of creationism (e.g., the theocratic motives behind creationist policies, the absurdity of letting scientific truth be a matter of majority rule).

This is where something like the Flying Spaghetti Monster can be incredibly effective. When a school board is considering forcing a sectarian set of religious claims into a classroom, as is the case for any sort of creationism, even ID creationism, something like the FSM highlights how selective that policy is, and the absurd consequences that would follow if the policy were applied fairly to all religious ideas. Any argument against admitting the FSM can instantly be turned around as an argument against teaching creationism, and gives a chance to highlight the differences between scientific methods and religious approaches. The danger is that it can read as a parody of religion itself. In the context of official policies that promote one religion over another, that last part is less of an issue, but in the case of people voluntarily attending an event which promotes pseudoscience, it’s a much bigger issue.

This is where something like the Flying Spaghetti Monster can be incredibly effective. When a school board is considering forcing a sectarian set of religious claims into a classroom, as is the case for any sort of creationism, even ID creationism, something like the FSM highlights how selective that policy is, and the absurd consequences that would follow if the policy were applied fairly to all religious ideas. Any argument against admitting the FSM can instantly be turned around as an argument against teaching creationism, and gives a chance to highlight the differences between scientific methods and religious approaches. The danger is that it can read as a parody of religion itself. In the context of official policies that promote one religion over another, that last part is less of an issue, but in the case of people voluntarily attending an event which promotes pseudoscience, it’s a much bigger issue.

Enough humorless maundering on the uses of humor, though. What are some of your favorite examples of humor or satire used to skewer pseudoscience?