The issue of whether Sherlock Holmes is science literate led to some fascinating discussion in the comments section, though not, I fear, to a consensus. But let’s turn to a matter closer to my own heart and examine what we can learn about someone’s science literacy based on whether they reject evolution.

I’ll introduce a distinction here that often occurs in the related literature between understanding evolution and accepting it. At least in theory, a person could accept evolution without understanding it, or could understand it but not accept it. One hopes that increasing understanding will lead to an increase in acceptance, but this is not always the case, alas. Those instances where people understand evolution but still reject it create tricky problems for defining science literacy. Even how to define the concepts of evolution acceptance and understanding gets tricky.

In general, understanding means having the ability to recite various facts about a topic when needed, signaling a general awareness of those facts. Acceptance requires something deeper, that the truth of those ideas is integrated into one’s thinking in some important way. So we might think of climate change acceptance as entailing changes in behavior to reduce the carbon pollution one produces, or at least that the climate consequences of one’s actions are taken account of in the decisionmaking process. Climate change understanding might mean that someone is aware that carbon pollution causes climate change, and that climate change is bad, but not necessarily recognizes how those ideas connect to one’s own life or to information from other fields. People make fewer decisions based on an understanding of evolution, so it’s harder to make that distinction operational for research purposes.

Consider a paper that came out in Evolution: Education and Outreach just last week. Leslie Rissler, Sarah Duncan, and Nicholas Caruso, all of the University of Alabama, surveyed 3000 students from the school about their views on evolution and on several related topics that shape people’s views on evolution. To assess acceptance of evolution, they used a standard questionnaire called MATE (Measure of the Acceptance of the Theory of Evolution). The survey asks for people's responses to 20 statements, of the form “The age of the Earth is at least 4 billion years” and “Modern humans are the product of evolutionary processes that have occurred over millions of years.” These are generally about matters of fact, though some probe the relationship between people’s scientific and religious views, like “The theory of evolution cannot be correct since it disagrees with the Biblical account of creation.” They also used questions from the Knowledge of Evolution Exam (KEE), a widely-used questionnaire drawn from questions college professors in Minnesota used in their exams, aimed at measuring knowledge of evolution separate from acceptance. Rissler and her colleagues reported that “students who had a higher acceptance of evolution (i.e., higher MATE score) tended to have higher knowledge scores on the KEE portion of the survey.”

Furthermore, University of Alabama students who said that their high school only taught evolution had much higher scores on both MATE and KEE than did students who said they were taught only creationism, both, or neither. By the time they are college seniors, students taught neither have generally caught up with those taught only evolution, while those taught creationism on its own or combined with evolution remained behind their colleagues throughout the four years of college. A complicating factor here is that students may misremember their schooling to conform with their own preferences: pro-evolution students may write creationist lessons out of their memories, while creationist students might insert them when they didn't happen.

More important than educational background, or any other factor, though, was a student’s religious views (whether they believe in God) and how often they attend church. While the educational variables had statistically significant effects, the model was vastly dominated by the students’ religious identity. And that’s pretty typical in such surveys, to the point that some people want to separate evolution questions out of general science literacy questionnaires, arguing that those questions serve as proxies for religiosity rather than science literacy (which brings us back to the Sherlock Holmes question).

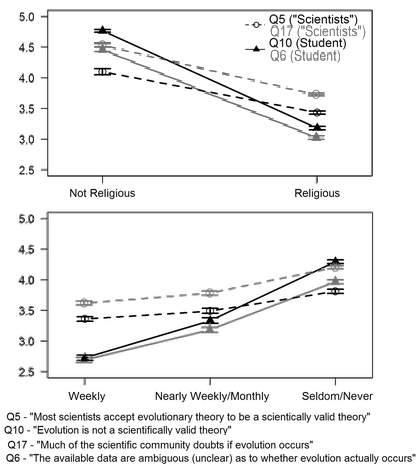

Figure 4 from Rissler, et al.'s paper. I overlaid all four questions to ease comparison. More religious students are less likely to agree that evolution is true, or that scientists think evolution is true. They are more likely to agree that scientists think evolution is correct than to accept it themselves, while less-religious students are more likely to accept evolution themselves than to think that scientists accept it.

Figure 4 from Rissler, et al.'s paper. I overlaid all four questions to ease comparison. More religious students are less likely to agree that evolution is true, or that scientists think evolution is true. They are more likely to agree that scientists think evolution is correct than to accept it themselves, while less-religious students are more likely to accept evolution themselves than to think that scientists accept it.To investigate that distinction, the researchers in Alabama looked specifically at a contrast between items in MATE that distinguish what students personally think the evidence supports, versus items asking what students believe scientists think. They figured students who understand the science but don’t accept it would be more willing to say that scientists think evolution is true than that they personally think it’s true. And indeed, that seems to be the case. Religious students were less likely to agree with either statement, but were more willing to grant that scientists accept evolution than to personally endorse evolution.

Oddly, the nonreligious were more willing to endorse evolution personally than to grant that many scientists endorse it. I asked Leslie Rissler about that issue, who acknowledged it is “somewhat peculiar.” She added: “I’m not sure why that is,” but wondered if it had to do with the way students understood the qualifier “most.” Or it may be a form of college-student arrogance, she suggested: “They may think they understand the science better than an unidentified group of ‘most scientists,’ a group that could include those pushing ‘intelligent design’ or similar poor ideas.”

I found a similar pattern in data from a Pew poll some years back. In that case, people were asked if “humans and other living things have evolved over time” and if “scientists agree that humans evolved over time.” It would make sense for people to either agree with both claims, or disagree with both. And I could understand how a creationist might reject the first but grant the latter (believing that scientists are blinded by their godless assumptions, etc.). But in that instance, just as many people took the contrary stance of personally agreeing with evolution while thinking that scientists don’t agree about evolution. I didn’t have a good explanation for the pattern then, and I don’t now (and the Pew question didn’t use the same “most scientists” phrasing as the Alabama study, so Rissler’s first suggestion wouldn’t apply, and it was a survey of the general public, so it isn’t just a question of college student behavior).

All of which returns us to the question of what science literacy means. I think we can all agree that someone who personally accepts evolution and knows that scientists do too is more science literate than someone who disagrees on either or both points. But if someone knows that most scientists accept evolution, but personally rejects it, are they more or less science literate than someone who personally accepts evolution but doesn’t think it’s accepted by scientists? What standard do we use to parse out those different aspects of science literacy?