I was reading Clarence Darrow’s autobiography, The Story of My Life (1932), recently. It was engaging, although no doubt all of the obvious caveats about the objectivity and accuracy of autobiography apply. Three chapters are devoted to the Scopes case: chapter 29, “The Evolution Case,” which discusses the preparations for the trial; chapter 30, “Science versus Fundamentalism,” which runs from the beginning of the trial to Darrow’s calling William Jennings Bryan to the stand to testify on religion; and chapter 31, “The Bryan Foundation,” which discusses Bryan’s testimony, the verdict, and the appeal. None of that contained anything that was particularly novel to me. At the beginning of chapter 45, though, I found a further reference to Darrow’s interest in evolution that I hadn’t expected to see, although I should have remembered it from Ray Ginger’s Six Days or Forever? (1958), which mentions it briefly.

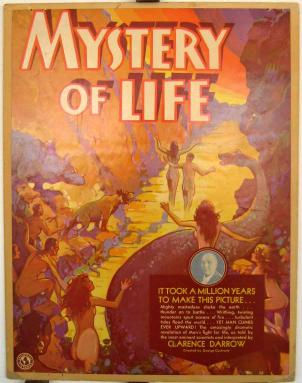

“In the summer of 1931,” Darrow writes, “I had the opportunity to carry out an idea that had been in the back of my head for years—I wanted to help prepare a ‘movie’ giving the main proofs of evolution, so far as it could be presented on the screen.” The result was The Mystery of Life (1931). He modestly adds, “whether it will prove to be a success I cannot say; for the present it is well received and favorably reviewed and well attended.” (The reviewer for The New York Times liked it, at least, pronouncing, “The picture is excellent in the way it presents its material—the history of life. It is constructed clearly and with due regard to the steps of the evolutionary doctrines, and if the lectures seem occasionally to be proving their contentions rather blandly, that is their purpose.”) As you might expect, though, Darrow—not a scientist himself—wasn’t the only begetter of the film. There was also the zoologist Howard Parshley.

A fascinating figure in his own right, Parshley was born in Maine in 1884 and educated at Harvard University, from which he received his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. After teaching zoology at the University of Maine for three years, he moved to Smith College, from which he retired in 1952, the year before his death. Professionally, he was a leading expert on the Hemiptera. He also wrote voluminously for the popular press, including The American Mercury (he was a friend of its cofounder H. L. Mencken) and the New York Herald Tribune, for which he reviewed books for two decades. He is perhaps best known, however, for his translation of Simone de Beauvoir’s feminist classic Le Deuxième Sexe (1949), published in 1953 as The Second Sex. Although needed, the translation was not really satisfactory, omitting about fifteen percent of the original and making a variety of mistakes; Beauvoir herself complained about it.

Anyhow, it was Parshley who wrote the screenplay for The Mystery of Life, directed by George Cochrane. The film opens with Darrow and Parshley in conversation: as the Times review noted, “Professor Parshley gives most of the actual scientific material; Mr. Darrow contenting himself mainly with the whimsical, pessimistic remarks for which he is known.” As for the footage, Ray Ginger summarizes, “Running over much of the same ground as the scientific testimony at Dayton, the film basically offered first-rate nature photography from this country and Europe.” The Mystery of Life apparently contained a lot of footage salvaged from previous films, including The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1918), which featured a battle between a Tyrannosaurus and a Triceratops; The Lost World (1925), the adaptation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s dinosaur adventure novel; and the German documentary Wunder der Schöpfung (1925).

Despite its deliberately bland presentation of evolution, The Mystery of Life was controversial even before its release. According to a piece in Time magazine in 1931, the New York State Board of Censors, charged with banning any film that was “obscene, indecent, immoral, inhuman, sacrilegious or of such character that its exhibition would tend to corrupt morals or to incite crime,” was horrified, telling the producers:

Eliminate all views of snails on actual cross fertilization. ... Eliminate ... ‘Here are two single celled animals in conjugation. Notice that the protoplasm, the living substance, is flowing from one to another.’ ... Eliminate all views of embryo ... actual copulation of female mantis ... views of spiders actually mating ... views of child at mother’s breast and view of bare breast ... view of children where sex is exposed. ... Reason: INDECENT.

The same piece quoted Darrow’s response (presumably directed to Samuel Cummins, the president of Classic Productions, who had approached Darrow about making the movie):

Absurd and the censors know it. ... Pictures of the Holy Mother nursing her infant abound all over the world. ... The story of the praying mantis is published everywhere. ... The human embryo is in any number of textbooks. ... Can’t you argue with them? If not, my personal inclinations would be for a fight.

According to Thomas Doherty’s Pre-Code Hollywood (1999), Harlan T. Horner, assistant commissioner of education for New York, defended the decision by explaining:

What constitutes decency in a plan of general public amusement open to both sexes and all ages may be vastly different from what constitutes decency before a restricted audience brought together for scientific or educational purposes … In this case, the presentation of such views taken in connection with the explanation of them in a public moving picture house, wholly unrestricted, constitutes indecency.

On appeal, however, the New York censors relented, reinstating all of the objectionable material except for certain scenes dealing with snails and spiders. Yet that wasn’t enough for all markets. Perhaps it isn’t surprising that when the movie was shown in Dayton, Tennessee, the local association of ministers called for a boycott, complaining that it was “anti-Biblical and anti-Christian.”