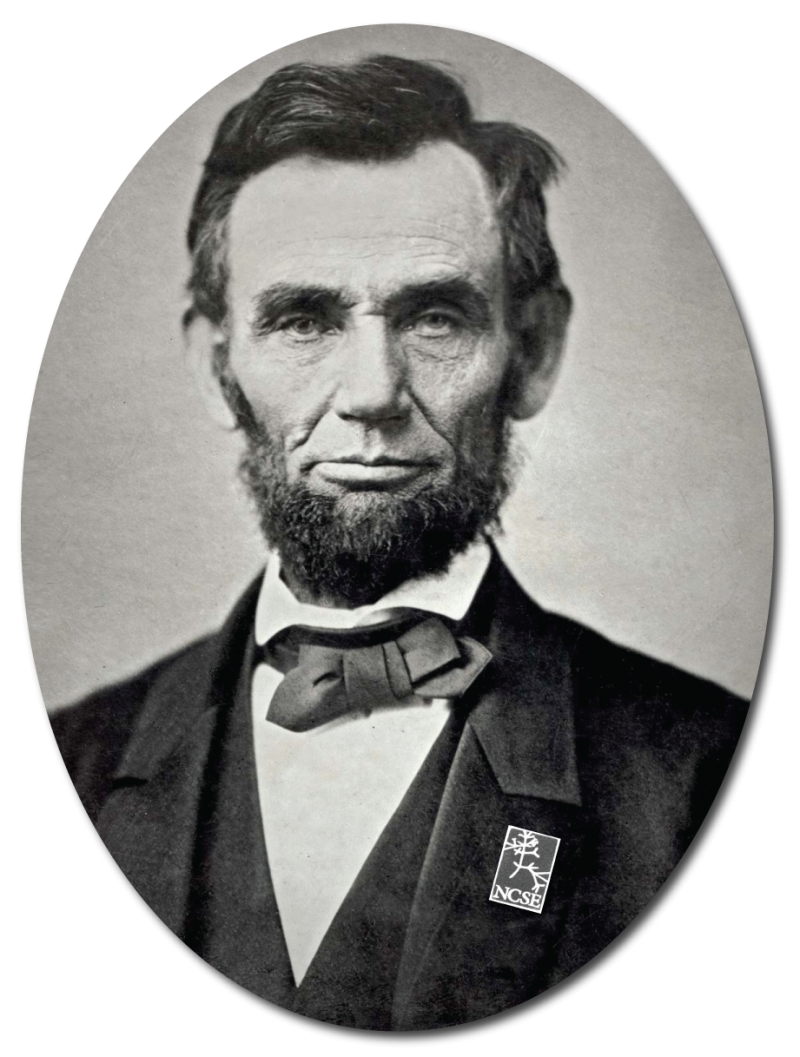

Last Wednesday was Darwin’s 205th birthday! Happy (belated) birthday, Chuck! It should come as no surprise that all of us here at the National Center for Science Education had our party hats on last week. But you might be surprised to learn that while we were toasting Darwin, we were also lifting our glasses to Abraham Lincoln, who was born on the Very Same Day—February 12, 1809. And today, Presidents’ Day, we get to celebrate Lincoln again.

And why would we be toasting Lincoln, you might ask? Was he a secret Darwin fan? What, if any, was his opinion on punctuated equilibrium? How about molecular evolution? Would he have preferred the neutral theory or the nearly neutral theory?

I don’t know the answers to the latter three questions. Although Lincoln’s intellect was legendary and he read widely, I doubt if he had time to think critically about whether Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species (which was published in 1859) was the most compelling contemporary explanation of the diversity of life on Earth. After all, he had an awful lot on his plate.

Here at NCSE, we raised our glasses to Lincoln because at the same time that he was burdened with overseeing the most terrible conflict our nation had ever experienced, he found the time to establish two organizations that were dedicated to bringing the best possible science to bear on matters of critical national importance.

The first was the Army Medical Museum, founded by William A. Hammond, whom Lincoln appointed Surgeon General of the U.S. Army in April 1862. The Museum was established as a repository of specimens for the study of the injuries and diseases confronting doctors and surgeons on the battlefields of the Civil War. Artists and photographers were assigned to field hospitals to document injuries and surgical techniques. During the war, these materials were shared among field hospitals to disseminate new techniques. After the war, the information was compiled and published as The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, 1861–65 (published in six volumes between 1870 and 1888). For more than another century, the Museum continued to collect and analyze samples, developing new techniques for studying and cataloguing them, eventually narrowing its focus to pathology samples and changing its name to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

As it happens, I have a very personal connection with the AFIP. I worked there from 1989 to 2004. Among the many pathology samples collected between 1862 and the present were 77 lung biopsies from American soldiers who died of the great influenza pandemic of 1918. From those biopsies, my colleagues and I were able to extract the genetic material of the killer influenza virus and determine its sequence. Were it not for Lincoln’s foresight in establishing a repository for medical specimens, those samples might never have been collected, catalogued, and preserved. And we might never have been able to learn the details of a virus that killed 20 to 50 million people.

Less than a year after appointing Hammond and the foundation of the Army Medical Museum, Lincoln signed into law a bill for the incorporation of the National Academy of Sciences. The charter of the NAS called for its elected members—the nation’s fifty most eminent scientists—to provide expert advice to the government on matters of science and technology. The NAS now has about 2,200 members, all scientists who have been elected by their peers, and many of whom have been called upon, just as Lincoln envisioned, to provide objective scientific advice upon the government’s request. The U.S. is unique in having this established method of drawing on the nation’s scientific talent—and we owe that valuable institution to Abraham Lincoln’s vision.

As it happens, NCSE has several personal ties to the National Academy of Sciences. Bruce Alberts, who serves on NCSE’s Advisory Council, was President of the National Academy of Sciences for twelve years, from 1993 to 2005. During that time, he was a tireless advocate for the importance of science education. Second, I worked at the National Research Council as a program officer for five years, where I had the privilege of working closely with some of the nation’s most eminent scientists to provide advice on issues in the biological sciences. Finally, Eugenie C. Scott, NCSE’s recently retired founding executive director, has served on several NRC committees and currently serves on the committee that advises the Division on Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education.

Abraham Lincoln was not a scientist, but clearly he greatly respected science, and valued the advice of scientists. While he apparently never seriously read anything by Darwin, I find it impossible to imagine that he would not have been fascinated with the conclusions that Darwin drew on the basis of his careful consideration of the specimens he collected on his voyages and the experiments he carried out himself.

It turns out that I have spent the bulk of my career working for organizations that were founded by Abraham Lincoln. I admit that, strictly speaking, he did not have anything to do with founding NCSE. But I don’t have any doubt that he would value it for its role in ensuring that children learn real science.

So happy birthday and happy Presidents’ Day, Abe, from all of us here at NCSE.