Why are people creationists? Like most of my colleagues at NCSE, I get that question a lot. Chris Mooney recently summarized some of the psychological research relevant to that question in a recent post at Mother Jones. “Our brains,” he writes, “are a stunning product of evolution; and yet ironically, they may naturally pre-dispose us against its acceptance.” Why? Because evolution contradicts many of our intuitions and cognitive biases. He lists seven major factors:

- essentialism: that each species is utterly distinct from all others

- teleology: that things exist for a grand purpose, while evolution does not entail any such purpose

- hyperactive agency detection: seeing a conscious intent behind the arbitrary and thoughtless events around us (faces in clouds, the dice being against us, a giraffe’s neck stretching so it can reach inaccessible food)

- mind-body dualism: that thought and consciousness are distinct from our physical form

- inability to comprehend vast time scales

- group identity: protecting one’s place in a (religious) community, which sometimes requires rejecting evolution

- avoidance of uncertainty and doubt: being asked to think about death or causes of uncertainty in one’s life makes people less likely to accept evolution, and increases religiosity.

In short, a lot of the same processes that predispose people towards religion also predispose people to being skittish about evolution. Or at least that’s true of Americans, the subjects (I believe) of all the studies cited.

But Americans are weird about evolution. Reviewing research on a standard science literacy questionnaire, a National Science Foundation workshop in 2011 reported:

Nick Allum showed…that the evolution item is more “difficult” in the US than in the UK (that is, one needs to have a higher level on the knowledge scale in order to answer it correctly). It is also a relatively weak discriminator for overall science literacy in the UK, but a much stronger one in the US.

A 2006 analysis of international attitudes towards evolution, published by Jon Miller, NCSE’s Genie Scott, and Shinji Okamoto in Science, found that religion was far less important in explaining differences in evolution-acceptance in European countries than in the US (where it, along with educational attainment, is the dominant predictor of anti-evolution sentiment).

This isn’t totally surprising. The creationist movement was born in America, and as Michael Lienesch observes in In The Beginning, it operates as a core component of the fundamentalist movement, a key marker of religious and political identity. I’d expect to see different results from several of the tests Mooney describes if they were run in other countries without that ninety-year history of creationist identity politics. America’s history, especially post-Scopes but also going back to our frontier mentality, the competition between religious denominations unfettered by a state church, and the quirks of our hyper-local educational system, surely play major roles in explaining why creationism emerged here and remains such a politically potent force.

Which brings us to Jerry Coyne’s response to Mooney’s report. Coyne is an eminent evolutionary biologist, but his dabblings in social science are far less impressive. He sees Mooney’s article as an attempt to “downplay religion as a cause of creationism,” even though, as Jason Rosenhouse observes, Mooney’s argument links creationism and religion throughout:

I don’t know what article Jerry read. I don’t see how Mooney could have been clearer that he thinks religious belief tends to make one hostile towards evolution. As Jerry notes, it’s right there in the subtitle. The juxtaposition is also pretty obvious from the article’s introduction.

But Coyne has an agenda. He doesn’t want to conclude that anti-evolutionism and religion are both driven by innate biases that the human brain evolved over the generations. He wants to conclude that religion qua religion makes people reject science, and therefore is bad. To do that, he wants to toss out the empirical work Mooney cites, work focusing on how individuals respond predictably to certain stimuli that make religion appealing and evolution less so. He instead focuses on a correlation among nations.

There are several problems here. First, correlation is not causation, so the empirical correlation he observes is not really at odds with the more detailed model Mooney is proposing. The empirical correlation could mean Coyne’s “religion is teh suxx0rs” model is right, but it could also mean that religiosity and anti-evolution attitudes are driven by a shared, underlying factor. Second, he’s trying to use national trends to explain individual beliefs. This is called “ecological correlation,” and introductory statistics books all spend some time explaining how this can go astray.

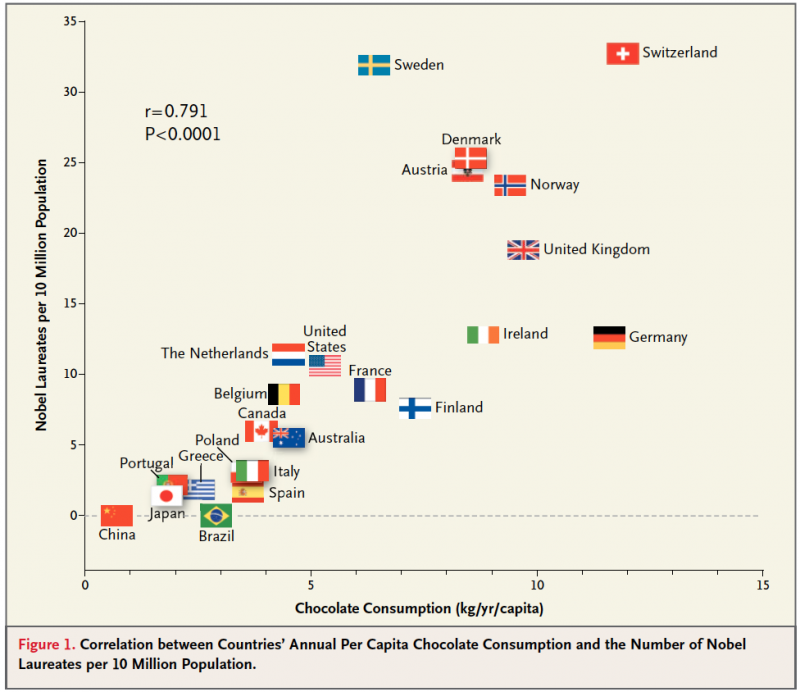

Here’s a recent example, and it involves cats, so Coyne may like it. Cats are known to carry a parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. The parasite’s life cycle also takes it through mice and rats (via ingestion of cat feces, or other food contaminated by cat feces), who get eaten by cats and thus complete the cycle. In rodents and humans, the parasite enters the brain, and may change the behavior of the host, making them less fearful and risk-averse. Toxoplasma infections can cause severe brain problems in developing fetuses, and pregnant women are urged to steer clear of cats and cat feces as a result. Some researchers wondered whether cat ownership might cause other brain problems in adult humans, and they found a correlation between national rates of Toxoplasma infection and national rates of brain cancer. But a look at 600,000 British women over 50 found no difference in brain cancer rates between those who own cats (and are thus more likely to be exposed to the parasite) and those who don’t (cheers to ScienceNOW for the story).  The correlation between nations may well be real, but it isn’t any more meaningful than the fact that countries which consume more chocolate win more Nobel Prizes per capita. In both cases, broader cultural factors are probably at work, including correlations between disposable income to buy treats and national investment in research infrastructure, and correlations between economic and medical development with changes in pet ownership and rural lifestyles.

The correlation between nations may well be real, but it isn’t any more meaningful than the fact that countries which consume more chocolate win more Nobel Prizes per capita. In both cases, broader cultural factors are probably at work, including correlations between disposable income to buy treats and national investment in research infrastructure, and correlations between economic and medical development with changes in pet ownership and rural lifestyles.

Correlation is not causation, and ecological correlation is not reliable. Ecological correlation is especially unreliable when the relationship between the variables changes between aggregated units (nations, in this case). And as discussed above, the relationship between religion and attitudes toward evolution does differ between nations. In particular, Miller, Scott, and Okamoto’s results compared individuals within nations and found that the effect of religiosity varied; Coyne used their national data to build his ecological correlation, even though the paper’s own analysis shows why that’s inappropriate.

Coyne’s idea that religion qua religion makes people anti-evolution is also less explanatory than the approach Mooney takes. If religion inherently makes people anti-evolution, then we need some special explanation for people like Francis Collins or Ken Miller or the 13,000 US Christian clergy who have endorsed evolution as fully compatible with their faiths. Nor does it explain the large and persistent differences in evolution acceptance among members of different faiths. On the other hand, if certain personality traits predispose people towards rejecting evolution and towards certain sorts of religions, that would generate testable predictions about the religions that would be the most anti-evolution, and the religions that are most friendly toward evolution. It even would suggest ways to reduce that conflict, both in how we present evolution and how religious communities discuss topics like teleology and, dualism, and how evolution-acceptance relates to group identity.

To really understand what drives individual beliefs and behaviors, national correlations aren’t enough, we need to talk about individual traits. That’s what the studies Mooney cites do, and anyone who wants to dispute those results should do so with comparable data.