Ever since reading Richard Holmes’s marvelous history The Age of Wonder, I’ve traced the links between poetry and science. While Age of Wonder is a history of British science between the days of Newton and those of Darwin, Holmes had previously written about the poets of that era, such as Shelley and Coleridge (an early member of the British Academy for the Advancement of Science). He adds a lot to the scientific history of the era (when the elements were discovered, when the first new planet since the days of Ancient Greece was found) by showing how this amazing thing called "science" shaped the popular and literary culture.

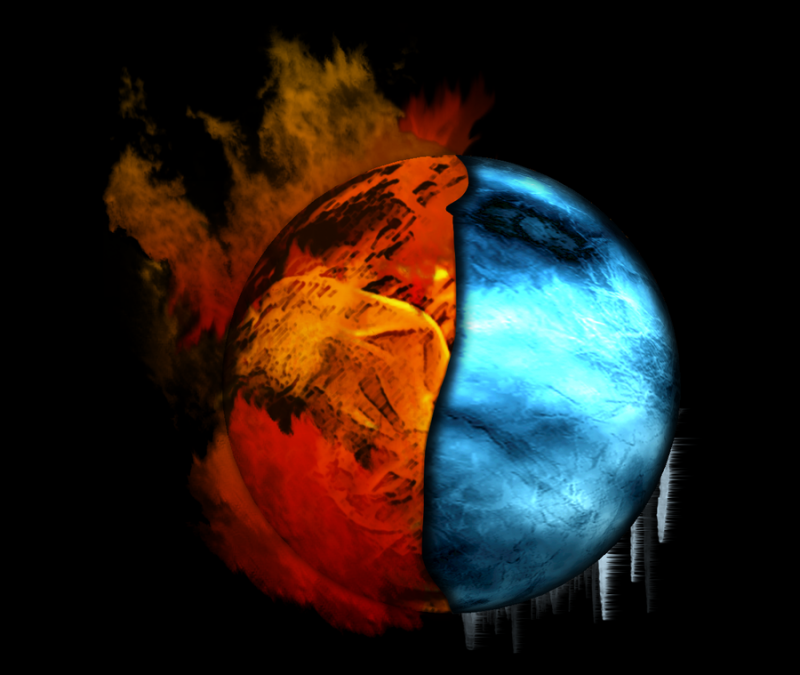

One of the more recent parallels I came across was a report that Robert Frost’s famous poem “Fire and Ice” was inspired, or at least informed, by Frost’s conversations with an astronomer. Before setting pen to paper, he apparently asked how the world might end, and astronomer Harlow Shapley told him that either the sun would gradually expand and burn the earth to a crisp, or the earth would drift away from the sun until it froze solid. “Some say the earth will end in fire,” Frost’s resulting poem opened, “Some say in ice.”

One of the more recent parallels I came across was a report that Robert Frost’s famous poem “Fire and Ice” was inspired, or at least informed, by Frost’s conversations with an astronomer. Before setting pen to paper, he apparently asked how the world might end, and astronomer Harlow Shapley told him that either the sun would gradually expand and burn the earth to a crisp, or the earth would drift away from the sun until it froze solid. “Some say the earth will end in fire,” Frost’s resulting poem opened, “Some say in ice.”

From there, Frost draws an analogy to the destruction wrought by desire and by hate, which took him beyond Shapley’s stellar expertise, and into the figurative language of poetry.

But that doesn’t mean it has to stay there. In researching that history, I came across some guidance from the Poetry Foundation about using Frost’s poetry in a science class. Some of it seems a bit abstract or difficult to build on, even if it does bring us back to climate change:

In a time when the Earth is threatened by the two specters of nuclear annihilation and global warming—which, ironically, might trigger an ice age if the polar ice caps melt and put the Gulf Stream out of business—“Fire and Ice” is an interesting place to start off the subject in science class.

This may all be true, but on its own, that insight doesn’t seem to inform our understanding of science or its relevance, nor would it seem to illuminate the poem itself. But the broader point stands, that Frost’s poems often illuminate something about why scientists do what they do, whether it be a farmer’s love for his land and desire to make it better, or a would-be astronomer’s belief that “Someone in every town / Seems to me owes it to the town to keep” a telescope since, “The best thing that we’re put here for’s to see; / The strongest things that’s given us to see with’s / A telescope.”

And much of that influence may well have come from Darwin and Darwin’s successors. Robert Faggen’s Robert Frost and the Challenge of Darwin traces the links between Frost and Darwin’s work, showing (apparently) compelling evidence that Frost considered Darwin’s work carefully and saw Darwin as an influence. As the Harvard Review sums up: “Frost, in ‘The Figure of a Poem Makes,’ tells us all about the differences between knowledge-gatherers, contrasting the scholar’s ‘conscientious thoroughness’ with the poet’s happenstance: ‘They stick to nothing deliberately, but let what will stick to them like burrs where they walk in the fields.’ We come away from Faggen’s book convinced that Darwin was among the largest burrs collected by Frost in his wanderings.”

One hopes that students would come out of high school wearing both Darwin and Frost among the burrs in their coat. The prospect that the two might be taught together thrills me, and I think it would even have thrilled my teenaged self.

The Poetry Foundation concludes their recommendations on Frost in science class: “Like science itself, Frost’s nature poetry is filled with discoveries. Like the best research, Frost’s poems take us beyond the facts to look at their implications. The orchard is not merely an orchard. It is something that starts us wondering about our places among the infinities.” It’s little wonder that poetry and science have such a long history of partnership, and I have little doubt that bringing poetry into a science class (or science into a literature class) would do a great deal to enhance both.

I’d love to hear more stories of successful classroom exercises like this, if anyone cares to share them in the comments.

Image:

"Fire and Ice" by 3amireh on DeviantArt, used under a CC:BY license.