I’ve always liked Tim M. Berra’s books, ever since, in college, I read his Evolution and the Myth of Creationism (1990), a wonderfully clear and succinct refutation of creationism. Berra focused mainly on young-earth creationism, since “intelligent design” wasn’t really on the radar yet, although “intelligent design” proponents now like to give him a hard time about what is admittedly a shaky analogy between the human fossil record and the sequence of Corvette models. Lately, he’s taken to biography, having written a similarly clear and succinct biography of Darwin, Charles Darwin: The Concise Story of an Extraordinary Man (2008)—just the ticket if the sight of Janet Browne’s magisterial but bulky two volumes makes your arms ache in anticipation of holding them to read.

I’ve always liked Tim M. Berra’s books, ever since, in college, I read his Evolution and the Myth of Creationism (1990), a wonderfully clear and succinct refutation of creationism. Berra focused mainly on young-earth creationism, since “intelligent design” wasn’t really on the radar yet, although “intelligent design” proponents now like to give him a hard time about what is admittedly a shaky analogy between the human fossil record and the sequence of Corvette models. Lately, he’s taken to biography, having written a similarly clear and succinct biography of Darwin, Charles Darwin: The Concise Story of an Extraordinary Man (2008)—just the ticket if the sight of Janet Browne’s magisterial but bulky two volumes makes your arms ache in anticipation of holding them to read.

Berra’s latest book is Darwin’s Children: His Other Legacy (2013), which offers brief biographies of all ten of Charles and Emma’s progeny, from luminaries such as George, Francis, and Horace to the short-lived Mary, Charles, and Anne, the apple of her father’s eye. Discussing Leonard Darwin’s work in economics, Berra writes of his 1897 book Bimetallism that, “It argued that the government ought to define the value of its monetary unit in terms of both metals [gold and silver], thus establishing a fixed rate of exchange between them.” So far so good. But Berra adds, deliciously, “As Miss Prism says in The Importance of Being Earnest, ‘When one has thoroughly mastered the principle of Bimetallism one has the right to lead an introspective life. Hardly before.’”

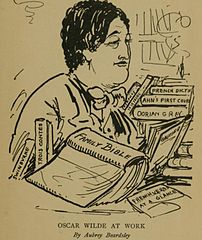

That reference to Oscar Wilde’s greatest play reminded me of a silly project that I began and abandoned around the time of Ernst Mayr’s death in 2005. Mayr, of course, was one of the greatest evolutionary biologists of the age, credited with the biological species concept, peripatric speciation, the foundations of modern philosophy of biology, and plenty besides. He was a prolific author, too, writing practically up until the year of his death—What Makes Biology Unique? was published in 2004. And he was a member of NCSE, naturally. It was sad, certainly, to hear of his death, but not entirely unexpected; he was born in 1904, after all. And my thoughts soon turned to what the inevitable posthumous appreciations would look like.

“The Importance of Being Ernst” sprang to mind as a headline for such appreciations—and with it, in one fell swoop, the project: rewriting Mayr’s contributions to biology in the form of Wildean epigrams. A challenge? Sure, of course. A pointlessly silly challenge? That, too. A pointlessly silly but nevertheless attainable challenge? Well, I didn’t find it so. Here’s about as far as I managed to proceed with my self-inflicted task. Mayr’s biological species concept, you’ll recall, defines species as groups of interbreeding natural populations that are reproductively isolated from other such groups. Trying to render that as a Wildean epigram, I managed the following: “A species, my dear Marquis, is like an unhappy marriage: consisting of only creatures that breed with each other.”

Fine, be that way; let’s see if you can do better. Anyhow, it occurred to me that I didn’t really know what—if anything—Wilde thought about Darwin. Born in 1854, he was educated (at Trinity College, Dublin, and Magdalen College, Oxford) in the 1870s, as Darwin’s ideas were still percolating through the British intelligentsia. But my exiguous knowledge of Wilde’s writing—limited to The Importance of Being Earnest and a handful of his other plays, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and a few of his short stories—didn’t suggest that he was particularly interested in biology. Nor did Richard Ellman’s 1988 biography (which I read hot off the press years ago, on a Greyhound bus between Boston and Columbus, Ohio, for reasons that needn’t detain us here) offer any insight on that score.

Naturally, my first stop was Thomas F. Glick’s What about Darwin? (2010), which, in the words of its Victorian subtitle, presents “all species of opinion from scientists, sages, friends, and enemies who met, read, and discussed the naturalist who changed the world.” Reviewing it for Reports of the NCSE a while back, I described it as “simply a delightful book to browse through,” in part because there are so many unlikely people to be found in it offering their views on Darwin. Marcus Garvey? Sherlock Holmes? Joseph Stalin? Yes, indeed. (But not, as I complained, Hilaire Belloc, who would have been worth including because his attack on H. G. Wells’s exposition of evolution apparently prompted no less a figure than John Maynard Smith to study natural selection.)

Glick didn’t disappoint me, quoting, from “The Critic as Artist” (1891), a passage in which Wilde writes:

The English mind is always in a rage. The intellect of the race is wasted in the sordid and stupid quarrels of second-rate politicians or third-rate theologians. It was reserved for a man of science to show us the supreme example of that “sweet reasonableness” of which [Matthew] Arnold spoke so wisely, and alas! to so little effect. The author of the Origin of Species had, at any rate, the philosophic temper. [...] Ethics, like natural selection, makes existence possible. Aesthetics, like sexual selection, make life lovely and wonderful, fill it with new forms, and give it progress, and variety and change.

Well, that suggests that Wilde admired Darwin a bit, although frankly I don’t quite understand the "ethics is to aesthetics as natural selection is to sexual selection" comparison.

That suggestion is confirmed by the sole item in The Letters of Oscar Wilde (1962), edited by Rupert Hart-Davis, to mention Darwin. In a letter of January 1889, Wilde thanked W. L. Courtney for sending him his short biography of John Stuart Mill, expressing his lack of interest in Mill by saying “A man who knew nothing of Plato and Darwin gives me very little...but Darwinism has of course shattered many reputations besides his.” Of course, Mill, who died in 1873, knew about Darwin, and devoted a long footnote in later editions of his System of Logic to “Mr. Darwin’s remarkable speculation”; in his posthumously published Three Essays on Religion (1874), he was inclined to reject natural selection in favor of intelligent design. But you get Wilde’s point.

Still, it wasn’t clear to me what, specifically, Wilde liked about Darwin. When I went to consult the full text “The Critic as Artist,” though, I discovered that Wilde was arguing (through the character of Gilbert) for the primacy of the critic over the creator—and, cosmologically, for the primacy of the Critic over the Creator:

The nineteenth century is a turning point in history simply on account of the work of two men, Darwin and Renan, the one the critic of the Book of Nature, the other the critic of the books of God. Not to recognize this is to miss the meaning of one of the most important eras in the progress of the world. Creation is always behind the age. It is Criticism that leads us.

It was Renan whose Vie de Jésus (1863) depicted Jesus as mortal, not divine, rejected the miracles of the New Testament as myth, and called for the Bible to undergo the same scrutiny as any historical document. His first name—I can hardly bear to type it—was Ernest. Well, as someone once said, “Life imitates Art far more than Art imitates Life.”