Don’t ask why, but I was reading Philip Larkin’s Required Writing over the weekend. As the title jokingly suggests, it’s a collection of pieces “produced on request,” as Larkin explains in his preface. Larkin, of course, is the English poet and novelist famous for his glum lyricism; in a 1979 interview reprinted in the book, he said, “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth.”

Don’t ask why, but I was reading Philip Larkin’s Required Writing over the weekend. As the title jokingly suggests, it’s a collection of pieces “produced on request,” as Larkin explains in his preface. Larkin, of course, is the English poet and novelist famous for his glum lyricism; in a 1979 interview reprinted in the book, he said, “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth.”

Anyhow, one of the pieces in Required Writing, dated 1971, takes as its topic A. E. Housman’s copy of The Golden Treasury: Second Series, selected by Francis T. Palgrave. The Golden Treasury purported to be a selection of the greatest poetry in the English language, and its second volume was intended to bring the collection up to date, as of 1897, the year in which Palgrave died and the second volume was published.

Why was Housman’s copy interesting? Larkin explains, “no less than 41 poems are neatly yet decisively deleted” with “a pencil line ruled vertically down the centre of the poem.” There may have been something personal about it: Housman’s A Shropshire Lad was published in 1896, and nothing from it was included in Palgrave’s selection of “the finest work of our greater Victorian poets.”

Larkin liked Housman’s poetry, perhaps because he found him simpatico: “Think of me as A. E. Housman without the talent or the scholarship or the soft job or the curious private life,” he told the novelist Barbara Pym. But he may have found Housman’s reaction to Palgrave especially interesting since he was then at work editing his own anthology, The Oxford Book of Twentieth Century English Verse, published in 1973.

Okay, but why am I mentioning it on the Science League of America blog? Well, I was skimming through Larkin’s list of Housman’s poems-to-be-deleted when I saw a familiar name: G. J. Romanes, Simply Nature (“Be it not mine to steal the cultured flower”). And again, G. J. Romanes, Home at Last (“Now more the bliss of love is felt”). G. J. Romanes? Was that Darwin’s disciple George John Romanes?

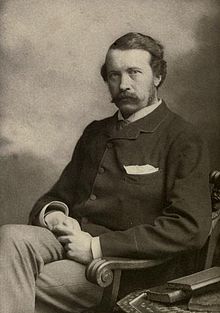

Indeed it was, although you wouldn’t know it to read the Wikipedia entry on Romanes. There you’d learn that Romanes was born in Ontario in 1848, graduated from Cambridge University (where he came to Darwin’s attention), and “tackled the subject of evolution,” expanding and refining Darwin’s theory (and coining the term “neo-Darwinism” to apply to views that, like Wallace’s and Weismann’s, emphasized selection).

Romanes also founded a lecture series at Oxford University, still running. His friend Thomas Henry Huxley was the second Romanes Lecturer, in 1893, speaking on “Evolution and Ethics.” The topic of the lectures isn’t limited to biology, though, so lecturers have included such luminaries as Winston Churchill, Isaiah Berlin, and Saul Bellow—as well as a pair of further Huxleys, Julian and Andrew.

But Romanes wrote poetry, too! A selection of Romanes’s poetry was published in 1896, two years after his death. The introduction says, “the poems here selected [are] intended to indicate rather than represent an aspect of the man without which his portrait and the record of his many-sided sympathies are incomplete, and to give in his own language some illustrations of the tenour and history of his interest and his thought.”

The Selection is dedicated, by the way, to Palgrave: “in memory of his interest in the following poems and of his affectionate regard and respect for the writer.” I’m afraid that my sympathies are with Housman, though. Here’s a sample from Romanes’s privately published poem written in memory of Darwin—mercifully, only a quarter of it is contained in the Selection.

I weep not for thy giant mind;

Of thee that mind was but a part,

And if it had been uncombined

With all the greatness of thy heart

The heavy edge of Sorrow’s plough

Could not have trenched the heart it breaks;

Nor would my grief have been, as now,

A grief my deepest soul that shakes.

Ye who thus speak but know the grief

Of those who grieve that genius dies—

A sorrow distant, small, and brief,

Which may not even dim the eyes.

Still, my curiosity is sufficiently piqued that I think that I’ll have to plan to read Joel S. Schwartz’s Darwin’s Disciple: George John Romanes, A Life in Letters when I have a chance. Reviewing it in Reports of the NCSE, John M. Lynch wrote, “This volume deserves to be on the shelf of anyone—historian or not—with an interest in nineteenth-century biology.” If they have a big enough shelf; it’s almost eight hundred pages long!