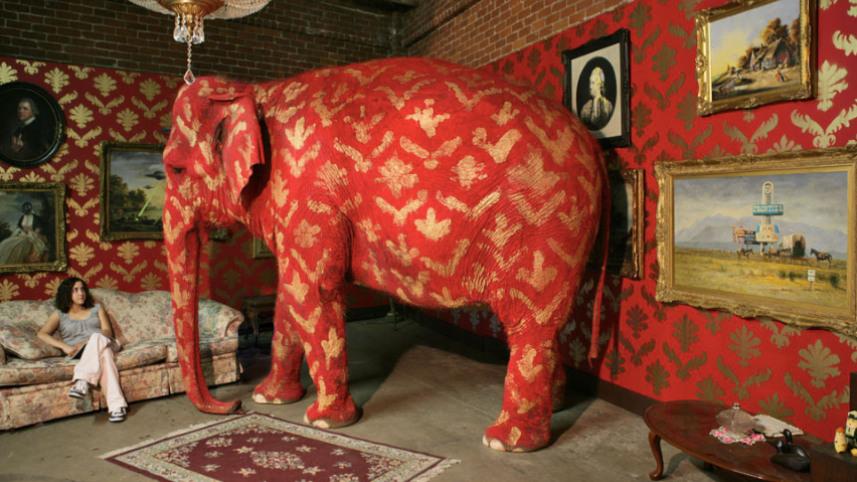

The Elephant in the Climate Change Classroom

Flickr Photo by Dunk. CC By-NC 2.0.

A recent article in Nature Climate Change gets much of the challenge and opportunities of teaching climate change exactly right—but sidesteps the denialist elephant in the room.

The article, “Promoting interdisciplinarity through climate change education” (subscription required), acknowledges that climate change, if covered at all in college, consists of “a few disconnected lectures in different courses” and they admit that knowledge and understanding of climate change in the US are “weak at best in the general public.”

Aaron McCright and his colleagues are indeed right in saying that climate change is “exceedingly difficult for educators to teach and for students and audiences of all ages to learn.”

But the reason we've struggled with climate change education in the U.S. isn’t just that climate change is complex and inherently interdisciplinary in nature. It’s also been the focus of two decades or more of deliberately seeded confusion and doubt mongering. More on that in a moment.

The thesis of the article is spot on: “teaching climate change to students a golden opportunity not only to improve their knowledge and understanding of a diverse array of issues encompassed by climate change, but also to promote interdisciplinary process skills that are paramount to solving twenty-first century problems.”

The authors encourage teaching climate change across the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) disciplines, integrating where possible with social sciences, using a variety of strategies such as problem-based learning (PBL), having students focus of the famous “hockey stick graph,” have a “climate change week” that makes use of existing online modules and activities, or even offering a “climate change semester or year” that would allow students to “actively discuss and perform inquiry-based learning projects with climate change data from their region.”

But the authors gloss over one of the key reasons why climate change is “exceedingly difficult for educators to teach and for students and audiences of all ages to learn”: years of deliberately manufactured doubt and denial about whether climate change is occurring at all and human activities are responsible that have been perpetuated by vested interests.

Largely due to their own lack of background or confidence in teaching climate change, some educators admit they teach “both sides” of the phony climate change controversy because they are pressured to do so or mistakenly believe it fosters critical thinking and argumentation skills of their students. Others avoid teaching climate change because they believe it doesn’t fit in with, say, biology or chemistry curriculum. Still others teach it hesitantly, skim over the essentials, or avoid the topic altogether.

McCright and his co-authors tout the fact that NASA and the National Science Foundation have generated a “torrent of research funding for climate change education research in recent years.” But much of that funding was tied to stimulus money allocated by Congress in 2009, and in fact this burst of funding—the first after nearly a decade of virtually no funding for climate change education from the federal government—has proven to be a brief boom and bust cycle, with very little dedicated funding for climate education left in the federal pipeline.

To be sure, the goal articulated by McCright et al. in their Nature Climate Change article is noble and imperative: promoting an interdisciplinary and integrating approach to climate change education—thereby encouraging interdisciplinary mastery of the causes, effects, risks and responses to climate change—that can also benefit people’s ability to address other 21st century challenges.

But let’s not underestimate the challenges—the lack of substantial funding and leadership and especially the depth of denial—that need to be met if we are going to be able to truly turn the tide.

And this just in. A new national poll from the University of Texas finds:

Children may also play a role in attitudes on climate change. Seventy-four percent of survey participants living with children under 18 years of age say that climate change is occurring, while just 62 percent of those living without children do.