A Camel Skull!!!How Can a Camel Skull Be Used in the Ministry?Take a look at the following three overheads. I think you will see how we can use even a camel skull to show that our pre-conceived ideas will influence how we see the world around us. Remember when you use these the audience will not know (usually) that it is a camel skull. 1. First show this graphic and have the audience give you feedback. ... Was this animal a flesh-eater, omnivore etc. Point out the "sharp teeth", what would this animal have used these teeth for? 2.Then show this next graphic. This is a drawing made showing what one person (the artist) thought the animal may have looked like. 3. Lastly, show this graphic of what the animal really was. Even though something has sharp teeth it doesn't necessarily "prove" that it ate meat. In the same way we have to have all of the information before we can know what happened in the past. Only God was there in the beginning and has told us what has happened. We have to trust Him when it comes to issues such as the origin of man, earth, the universe etc. These issues are outside of the realm of science and cannot be "proven". I hope these help! http://www.answersingenesis.org/Webman/Article.asp?Old=camskull.html |

The School and Students

This course fulfilled a basic science requirement for students at Madison (WI) Area Technical College (MATC). There were no prerequisites, and most of the students would not go on to specialize in any area of the sciences. In short, this could be the last or the only science education many of these students would receive. Most of the students were adults returning to school after a number of years or recent high-school graduates whose grades, prior scholastic preparation, or financial situation precluded matriculation at a baccalaureate institution. Most of these students were in the "college-transfer" program, which meant that they hoped to transfer these credits to a school that granted a 4-year degree.

During the one-semester Animal Biology course, we explored the typical zoology topics — basic chemistry, cell biology, genetics, evolution, ecology, and comparative biology (anatomy, physiology, and behavior). Because MATC has a strong program for animal technicians, our teaching lab contained skeletons and mounted specimens of a number of species. We were also fortunate to have access to the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum to supplement our teaching. Athough the department had a staff to prepare specimens and schedule laboratory use, the small class size meant that all instruction — classroom, laboratory, field trips, and discussion sections — were led by the course instructor. There were 2 "sections" of the course — 16-17 students in each.

By the time I discovered the AIG materials in March, these students had already studied specimens at the UW Geology Museum and had begun comparative studies of skeletal materials in their laboratory sections. One of the assignments in that exercise was to examine skeletal material, including teeth, to understand the relationship between dental anatomy and behavior (including food sources). The AIG challenge to bring these images directly to these students seemed to me to be the ultimate "authentic assessment" of their learning and my teaching. If they could apply their "book learning" to this "real-life" situation, then they really did grasp the process that we call "science as a way of knowing" (SAAWOK). It was not without a little trepidation that I presented the AIG materials during the 2-hour discussion sections.

THE AIG MATERIALS

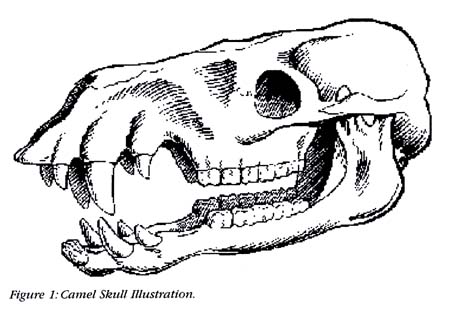

Figure 1: Camel Skull Illustration

Figure 1: Camel Skull Illustration

The first AIG overhead is a line drawing of the skull of a camel (see Figure 1). True to the AIG expectations only one of my students — a young woman from North Africa — knew what sort of animal this was (see sidebar). She agreed to sit on the sidelines and fill us in later on camel behavior and ecology and how they relate to the structures we observed. Also true to AIG expectations was the students' initial reaction — they focused immediately on the tall, pointed teeth in the front of the skull as I asked the what sort of food these animals ate. But then things changed.

These students with a minimum of prior instruction in comparative anatomy also noticed the molars — high, flat teeth which are typical of animals eating grasses and tough vegetation. One student remarked that, although the "anterior dentition" is impressive, it is really the back teeth which dominate the mouth. They seem more "important" to the animal than the few larger pointed teeth in the front.

Because they had already examined the dentition of flesh-eating, plant-eating, and omnivorous reptiles and mammals in the museum and lab, the students were able to see that the "sharp" teeth in the front of the jaw were not really sharp! The teeth were tall and narrow, but even the line drawing showed that they were blunt, not sharp.These students had seen large canines and incisors in plant-eating animals and knew that these were used in a variety of social and antipredator behaviors — not for eating meat. Furthermore, many were familiar with horses and deer and recognized that the combination of lower incisors with a bony "cutting board" in the upper jaw is useful for animals that bite off tough stems or grasses.

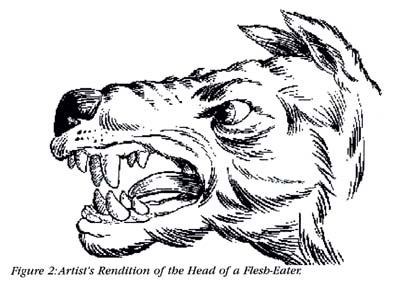

Figure 2: Artist's Rendition of the Head of a Flesh-Eater

Figure 2: Artist's Rendition of the Head of a Flesh-Eater

The discussion of the qualities of the skull lasted about 20 minutes, and then I introduced the second AIG image (see Figure 2). This artist's rendition of the living animal clearly presents the animal as a flesh-eater. After discussing the rendition in small groups for about 10 minutes, the students came up with 2 reasons to reject this image as inappropriate. The first was the shape of the mouth. One group noticed that the "lips" opened far back into the jaw. This is good for flesh-eaters which need to open wide to kill and tear chunks of flesh from their prey or which use teeth near the back of the jaw as a sort of "bone-cracker". However, for grazing animals, like camels, horses, and deer, that need to chew their food a lot, the "cheeks" help keep the food between the teeth while chewing. The mouth is smaller and the molars almost never show In this rendition, the students suspected that the half-chewed food would keep falling out of the animal's mouth.

Second, the students noticed that the front teeth were not "sharp" and that the lack of teeth at the front of the upper jaw would cause serious problems for any animal that needed to tear flesh or deliver a deep puncture wound to its prey. This animal had none of the sharp, piercing, slicing teeth needed to be a competent predator.

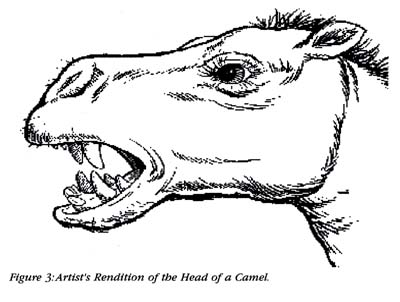

Figure 3: Artist's Rendition of the Head of a Camel

Figure 3: Artist's Rendition of the Head of a Camel

Then, following the AIG "lesson plan", I showed the students the artist's rendition of the camel's head (see Figure 3). All the students agreed within minutes that this head was the more likely fit. They were willing to hedge their bets as to whether the skull had to be a camel, but they clearly saw that the animal had to be a plant-eater and not a flesh-eater. Of course, they had already rejected the flesh-eater as a good fit solely on the basis of anatomical evidence. They had seen skulls of many animals and recognized that the dental anatomy in this animal was that of a plant-eater with special adaptations for "mowing" stems and grinding foods, not piercing and tearing.

At last, our North African student gave us a brief account of camels in her homeland. Once she explained how and what camels eat, their social organization, and their behavior, there was a "chorus" of nods and murmurs.

Reflection

An important part of the "discussion" sections in this class was a period for reflection on ideas and issues raised in the course or on the various learning activities, such as this one, that they engaged in. It is a classic SAAWOK component — what do we know and what makes us sure we know it? The students needed to identify the question(s) they were asking, the data available to them, what else they might need to know to answer the questions(s), and how to present their conclusions persuasively (for example, Stewart and Jungek 1995). An important part of this process is to identify the evidence and the materials used in the process and to explore how they influenced our conclusions (Petto and Petto 1997).

In this activity, the students recognized that the prominent front teeth had tended to attract their attention away from the other evidence and away from a more thorough examination of the anatomical features in the camel skull. This attraction, they agreed, prompted them to jump to conclusions about the nature of the organism before they had a chance to consider all the information available. Perhaps most important, the students recognized that a focus on the large front teeth caused them to put aside — at least temporarily — their previous knowledge and experience which were vital for solving the problem.

The AIG website invites us to "show that our pre-conceived ideas will influence how we see the world around us" without, of course, telling us that the AIG conclusions are derived from Genesis 1:30: "And to every beast of the of the earth, and to every fowl of the air, and to every thing that creepeth upon the earth, wherein there is life, I have given every green herb for meat." This is the passage that AIG Director Ken Ham uses in his lecture to "prove" that Tyrranosaurus rex was a plant-eater (See Skip Evans's "Creationism: A trip to the dark side" RNCSE 1998 Mar/Apr;18[2]:22-2). If abandoning the scientific evidence in favor of a 6000-year-old scriptural account doesn't constitute being influenced by "pre-conceived ideas", I don't know what does.

In the end, however, these students really came through and performed as AIG said they ought to — forming their conclusions on the basis of the evidence and not on "pre-conceived ideas". I couldn't have written a more appropriate and challenging final exam.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the students in my spring 1998 Animal Biology class at Madison Area Technical College. Without them, this outcome would not have been possible, but most of all, thanks for proving that you were learning something about the process of science as well as the data.