Summary of problems:

Scientists continue to research the origins of life, and to investigate the possibility that early lineages of life shared genes so freely that very early living things cannot be separated into multiple discrete lineages. The extent of that sharing is a subject of active research and scientific debate. Explore Evolution misrepresents that ongoing research as if it were between advocates of a single tree of life and supporters of a "neocreationist orchard."

Full discussion:

The nature of the Last Universal Common Ancestor is a topic of ongoing research today, and a book which intended to explore current scientific controversies within evolution would have to address that topic. A growing body of evidence suggests that there was so much sharing of genetic material among the single-celled organisms at the base of the tree of life that the different strands cannot be separated. Some scientists go so far as to treat the entire community of organisms alive at the time as essentially a single superorganism which shuffled genes freely between components. They treat that community of cells as the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). As particular genes became more tightly entwined with the functioning of other genes, the sharing decreased and lineages began to diverge.

Other scientists hold that gene transfer between organisms is not an obstacle to tracing the lineages of modern life, and insist that the branching trees of life can be traced all the way back to the earliest cell.

Explore Evolution ignores this ongoing and fascinating scientific controversy. To the extent they acknowledge its existence, it is only to misrepresent the views of participants in that debate. This statement, for example, betrays a profound lack of understanding of evolution and could hardly be more inaccurate or misleading about basic biology:

Darwin envisioned this 'Tree of Life' beginning as a simple one-celled organism that gradually developed and changed over many generations into new and more complex living forms.EE, p.6

A central point of the Origin of Species is that evolutionary change takes place in populations of organisms, not in individuals. To elide this point, or fail to make it clear, is obviously an egregious error in a book supposed to be about evolution.

Furthermore, even in 1859 Darwin allowed for the possibility of more than one type of early organism. At the end of The Origin of Species, for example, Darwin wrote:

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one;

Since then, the evolution of the earliest cells has been and continues to be a dynamic area of research.

Neo-creationist orchard: From Kurt Wise (1990) "Baraminology: A Young-Earth Creation Biosystematic Method," in Robert E. Walsh (ed.) Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Creationism, Vol. 2. Creation Science Fellowship, Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA. p. 345-360.Furthermore, Explore Evolution badly misrepresents the state of science when it states "Other scientists doubt that all organisms have descended from one and only one common ancestor" (p. 9). While some scientists dispute the strict monophyly of the early history of life, but only because they think that genes from other branches of the tree of life moved between lineages, not because they dispute that life can be traced to a common ancestor. Researchers in the field do not "say that the evidence does indeed show some branching groups of organisms, but not between the larger groups" (pp. 9-10, emphasis original), and scientists absolutely reject the notion that "the history of life should be represented as a series of parallel lines representing an orchard of distinct trees" (p. 10). In fact, that way of talking about life's history was originated by creationists, as shown in the figure at right. In describing his "orchard" view of life, young earth creationist Kurt Wise explains:

Neo-creationist orchard: From Kurt Wise (1990) "Baraminology: A Young-Earth Creation Biosystematic Method," in Robert E. Walsh (ed.) Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Creationism, Vol. 2. Creation Science Fellowship, Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA. p. 345-360.Furthermore, Explore Evolution badly misrepresents the state of science when it states "Other scientists doubt that all organisms have descended from one and only one common ancestor" (p. 9). While some scientists dispute the strict monophyly of the early history of life, but only because they think that genes from other branches of the tree of life moved between lineages, not because they dispute that life can be traced to a common ancestor. Researchers in the field do not "say that the evidence does indeed show some branching groups of organisms, but not between the larger groups" (pp. 9-10, emphasis original), and scientists absolutely reject the notion that "the history of life should be represented as a series of parallel lines representing an orchard of distinct trees" (p. 10). In fact, that way of talking about life's history was originated by creationists, as shown in the figure at right. In describing his "orchard" view of life, young earth creationist Kurt Wise explains: Some modern creationists are suggesting a metaphor of their own a metaphor which is planted between the Evolutionary Tree and the Creationist Lawn. The new metaphor may be described as the "Neo-creationist Orchard" (see figure 1C [reproduced here]). In this metaphor, life is specially created (as fruit trees are specially planted) and polyphyletic (i.e. each tree has a separate trunk and root system). There are also discontinuities between the major groups (trees are spaced so that branches do not overlap and could not and never did anastomose [grow together]) and there are constraints to change (a given tree is limited to a particular size and branching style according to its type). In these ways, the Neo-creationist Orchard is similar to the Creationist Lawn [Figure 1A]. They differ, though, in that the Neo-creationist Orchard allows change, including speciation, within each created group (each tree branches off of the main stem). Permitting this type of change (variously called by creationists 'diversification', 'variation', 'horizontal evolution', and 'microevolution') in different amounts in different groups allows the creation model to accomodate microevolutionary evidences (e.g. changing allelic rations, genetic recombination, speciation, etc.).Kurt Wise (1990) "Baraminology: A Young-Earth Creation Biosystematic Method," in Robert E. Walsh (ed.) Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Creationism, Vol. 2. Creation Science Fellowship, Inc.: Pittsburgh, PA. p. 345

In this passage, Kurt Wise introduces his explicitly creationist concepts in the exact terms that Explore Evolution uses. Dr. Wise, is undoubtedly one of the "critics" EE refers to, but he is never cited in EE. Not surprisingly, the book doesn't mention that the young earth creationist group Answers in Genesis states that the same figure shows "the true creationist 'orchard' model."

"Creation model": Explore Evolution co-author Paul Nelson's preferred "creation model," copied from a German creationist textbook.

"Creation model": Explore Evolution co-author Paul Nelson's preferred "creation model," copied from a German creationist textbook.Paul Nelson (2001) "The Role of Theology in Current Evolution," in Intelligent Design Creationism and Its Critics Robert Pennock, ed. The MIT Press:Cambridge, MA pp. 685.

Nor does the book point out that one author, Paul Nelson, previously presented the "polyphyletic" model shown at left, writing that "creationists defend the dynamic pattern of figure 32.2," rather than the models like the lawn illustrated by part a) of Wise's figure (Paul Nelson, 2001. "The Role of Theology in Current Evolution," in Intelligent Design Creationism and Its Critics Robert Pennock, ed. The MIT Press:Cambridge, Ma. pp. 684-685). Elsewhere, Nelson and a co-author defended their young earth creationist views by arguing that "The overall geometry of the history of life depict[s] a forest of trees, each with its own independent root" (Paul Nelson and John Mark Reynolds, 1999, "Young Earth Creationism" in Three Views on Creation and Evolution, J. P. Moreland and John Mark Reynolds, eds. Zondervan Publishing: Grand Rapids, MI. p. 45).

This vision of multiple trees of life, totally independent of one another is a creationist concept, and bears no relationship with any position being advanced in the scientific literature. There are challenges to the idea that diversity of life followed a strict branching pattern from the earliest days, but as shown in the figure at the right, this view rests heavily on exactly the sort of mixing (or "anastomosis") that Nelson and Wise reject. The figure EE uses to illustrate its proposed alternative view of life also does not include the complex exchanges of genetic information proposed by the authors Explore Evolution cites as critics.

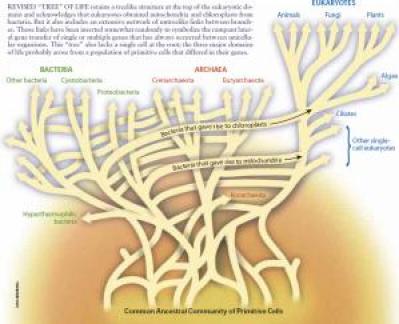

A modern view of the tree of life: From W. Ford Doolittle (2000) "Uprooting the tree of life." Scientific American, 282(2):90-5. Note that distances are not necessarily to scale in this image. This image reflects a view held by some practicing scientists (including Dr. Doolittle, the author of the original article) that there was a period in life's early history when genes swapped so frequently that it is impossible to treat those earlier lineages as truly distinct, nor to trace those lineages back cleanly to a single ancestor. They do not dispute that life has some common ancestor, but they do seek to clarify how we talk about that ancestor.

A modern view of the tree of life: From W. Ford Doolittle (2000) "Uprooting the tree of life." Scientific American, 282(2):90-5. Note that distances are not necessarily to scale in this image. This image reflects a view held by some practicing scientists (including Dr. Doolittle, the author of the original article) that there was a period in life's early history when genes swapped so frequently that it is impossible to treat those earlier lineages as truly distinct, nor to trace those lineages back cleanly to a single ancestor. They do not dispute that life has some common ancestor, but they do seek to clarify how we talk about that ancestor.The scientists cited as supporting this "orchard" view of life actually advocate a tree very different from the one illustrated by Explore Evolution (figure i:4). As the figure to the right shows, the group of scientists challenging traditional views of the tree of life are not proposing the sort of orchard that EE illustrates. Where EE and its creationist antecedents' embrace "discontinuities between major groups," the objection raised by the scientists EE cites actually object that there aren't enough connections between the branches of the tree of life.

These authors do not dispute that we can talk about a single common ancestor, merely that we should talk about it in a different sense. Doolittle explains:

As Woese [an author cited as a critic of monophyly by EE] has written, "The ancestor cannot have been a particular organism, a single organismal lineage. It was communal, a loosely knit, diverse conglomeration of primitive cells that evolved as a unit, and it eventually developed to a stage where it broke into several distinct communities, which in their turn become the three primary lines of descent [eubacteria, archaea and eukaryotes]." In other words, early cells, each having relatively few genes, differed in many ways. By swapping genes freely, they shared various of their talents with their contemporaries. Eventually this collection of eclectic and changeable cells coalesced into the three basic domains known today. These domains remain recognizable because much (though by no means all) of the gene transfer that occurs these days goes on within domains.W. Ford Doolittle (2000) "Uprooting the tree of life." Scientific American, 282(2):90-95

This is a nuanced view, one that high school students are ill-equipped to understand until they have a fuller grasp on the basic concepts of biology. As Doolittle observes, even "some biologists find these notions confusing." It is hardly reasonable to expect students who are still learning what the genome is to appreciate a debate about the ways that gene swapping between ancient bacteria would have produced the sort of communal superorganism Woese and Doolittle describe. It would pedagogically inappropriate for Explore Evolution to thrust students into the midst of that debate without any background or support. Indeed, many biology teachers would be ill-prepared to lead such a discussion. This does not excuse the failure of EE to accurately describe the nature of that scientific debate.

Woese and Doolittle do not advocate an orchard, they simply thing that the trunk of the tree of life cannot be separated into distinct strands. They are not opponents of evolution, and Explore Evolution does the authors they cite no favors when they misrepresent the underlying science. That loose treatment of the underlying science also would do students and teachers no favors. A truly inquiry-based text might be able to wring some useful educational lessons from the debate going on over the base of the tree of life, but it is doubtful that high school students would benefit from that highly technical discussion, and they could not use Explore Evolution to understand even the basic nature of that ongoing research.