Does Biologist Malcolm Gordon thinks that tetrapods arose multiple times and are therefore "polyphyletic"?

Summary of problems with claim:

Gordon and Olson's point is far narrower than Explore Evolution presents it, and is marred by the authors' inexperience with the field. Even if the problems raised were valid when the paper was written, substantial new material has been found which clarifies many of the issues, and which has spawned new research.

Full discussion:

Explore Evolution introduces this sidebar with a blatant error:

Scientists have long thought that amphibians were a transitional form between aquatic and land-dwelling life forms. Why? Because amphibians can live in both the water and on land. Yet, the fossil record has revealed at least two problems with this idea.Explore Evolution, p. 28

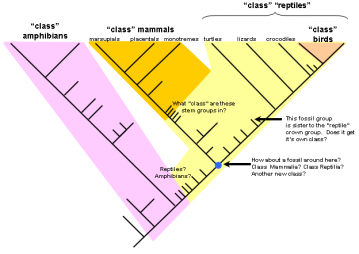

Tetrapod crown groups: with some fossil stem groups added, with an attempt made to map the Linnaean classes onto the stem groups. Fossil stem groups are very problematic for Linnaean ranks such as "class." Graphic by Nick Matzke. May be reproduced freely for nonprofit educational purposes.

Tetrapod crown groups: with some fossil stem groups added, with an attempt made to map the Linnaean classes onto the stem groups. Fossil stem groups are very problematic for Linnaean ranks such as "class." Graphic by Nick Matzke. May be reproduced freely for nonprofit educational purposes. Tetrapod crown groups with some fossil stem groups added, with an attempt made to map the Linnaean classes onto the stem groups. Fossil stem groups are very problematic for Linnaean ranks such as "class." The use of the term "transitional form" here is so vague as to be meaningless. As discussed above, this use of the term is hopelessly mired in a way of categorizing life that does not incorporate evolutionary thinking, and has been rejected by biologists precisely because of its ambiguity. For more on this shift in the way groups are named, see Appendix 2 and the figure at right. A traditional Linnaean classification would treat all the species in the area shaded pink as amphibians, while a modern classifications regard the amphibians as the major lineage branching off at the base of the phylogeny in the figure, and the species below that branch are regarded as "stem tetrapods," neither amphibians, reptiles, nor mammals. Similarly, the species before the split between reptiles and mammals are neither mammals nor reptiles, and are no longer referred to as "mammal-like reptiles," despite the use of that term in Explore Evolution.

This shift in terminology invalidates the first sentence of the sidebar (since the transitional form would not have been an amphibian, but a stem tetrapod from before the main split shown in the figure above). This also helps clarify the first supposed problem raised by Explore Evolution. The authors cite a paper by Gordon and Olsen authors who are not phylogeneticists and used terminology vaguely. When they make comments like, "no fossils are known that relate directly to the vertebrate transitions to land. No amphibious rhipidistian crossopterygians have been identified," they re speaking in the context of direct ancestors, a single fossil which has the properties of a certain group of fish ("rhipidistian crossopterygians") and the tetrapods. The tetrapods, however, share many traits with those fish, and treating these groups as totally separate is an inaccurate holdover from non-evolutionary classification schemes. Tetrapods are members of the same lineage as those fish, making the distinction Gordon and Olsen draw very ambiguous.

The book with the paper by Gordon and Olsen was published in 1995, with Everett Olson dying in 1993, meaning these chapters were written well over 15 years ago. Paleontologists these days do not speak in terms of direct ancestors i.e., that taxon x is the common ancestor of all tetrapods. There are 2 problems with such a claim: it is very difficult to demonstrate direct ancestry; and the fossils we have almost always have features uniquely derived within that group, telling us they were their own lineage. We are more likely to find something like an 'aunt' or 'cousin' as opposed to a 'parent,' 'child' or 'grandparent'. In other words, paleontologists do not claim to find direct ancestors, but instead find what are referred to as collateral ancestors or sister groups. Gordon and Olson working in an old and outdated methodology of viewing fossils as direct ancestors and their claim that no direct ancestor have been named in the vertebrate transition to land is meaningless no one claims there has been! The authors of Explore Evolution obscure these methodological revisions (either intentionally or through their own outdated understanding) and use Gordon and Olsen's claims to discredit recent research of the numerous sister groups that document this transition quite nicely. These sister groups are identified because they possess traits predicted to be present in the stem groups between modern forms and other known fossils. The sequence of changes in the anatomy of the skull, the legs and the shoulders match the sequence of hierarchal changes predicted by common descent.

There are thus two major problems with Explore Evolution s representation of tetrapod origins: (1) Gordon and Olson is long outdated, and Explore Evolution is using old quotes to discredit recent research they only vaguely mention "More recently, paleontologists have found fossils that seemed to show a connection between fish and tetrapods"; and (2) Gordon and Olson were operating in a scheme of classification which was not rooted in evolutionary relationships, and viewed the world in terms of direct ancestors, a view long abandoned by paleontologists. Explore Evolution's description of Gordon and Olsen's claims show exactly why it's important to stay up to date with recent research if you do not, you run the risk of misrepresenting a field and confounding long-outdated remarks with well established data. If the job of science education is to expose students to scientific methodology and hypotheses that explain the best and most recent data available, Explore Evolution certainly falls short of achieving such goals.

The second point Explore Evolution raises is that the earliest fossil tetrapods are too widely scattered, in Greenland, South America, Russia and Australia. Again, the evidence they cite is long outdated. In the words of Jenny Clack from a 1997 paper describing the evidence of South American tetrapods,

A single, isolated print from the Ponta Grossa Formation of Brazil was interpreted by Leonard (1983) as the left manus and its date was given as probably the base of the Upper Devonian. As an isolated block, there is room for doubt about this print's provenance and thus its date. As a natural cast, there is doubt about the circumstances in which the print was formed. Further doubt has been cast recently on its identity as a footprint. Rocek and Rage (1994) have commented on the description of this specimen working from a cast and photographs, and suggest that it is more plausibly interpreted as the resting trace of a starfish. until further material from the same locality comes to light, it should be treated with extreme caution as a record of a Devonian tetrapod. Furthermore, the specimen derives from an apparently marine environment which contains brachiopods (Rotek and Rage, 1994). Thus it would normally be considered as subaqueous in origin. This specimen provides no convincing evidence of terrestriality among Devonian tetrapods.Jennifer Clack (1997)

There is indeed good tetrapod evidence from the other locations. The current hypothesis is that tetrapods originated in the northern continents, explaining the fossil occurrences in Greenland and Russia areas which were, at the time, equatorial. But what about Australia? The Australian evidence consists of a lower jaw and trackways evidence that seems to be clearly of tetrapod origin. However, we don t exactly know where Australia was back 360 Ma. We have a good approximation, but of course in science, details matter! Thus, we re still working on establishing this question but that s how science works. New data opens new questions and gets people thinking. Far from being the unsolvable problem Explore Evolution presents, requiring the evolution of tetrapods multiple time in multiple places, this is an area where ongoing research in geology, and new paleontological digs, are allowing scientists to test hypotheses and refine our understanding. Explore Evolution presents a vision of science trapped by unanswered questions, the exact opposite of an inquiry-based approach, and the opposite of the way scientists work. [say more]