This post was written by Stephanie Keep and Peter Hess.

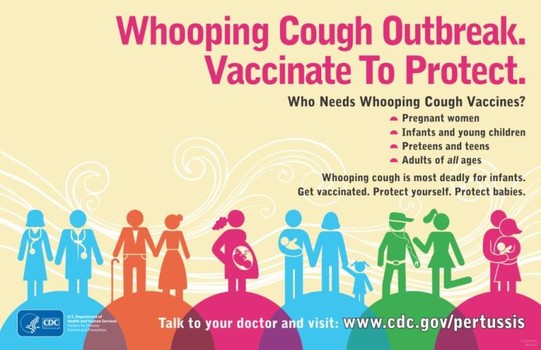

When comforting our children at the doctor’s office after a shot, we can say, “I know it hurts, but it’s better than getting sick.” Unfortunately, there are a lot of people out there who don’t feel the same way. California has just declared a whooping cough epidemic. More than 3400 children in California have been diagnosed since January 1, and there are potentially up to ten times as many unreported cases…of whooping cough. This is not just an annoying tickle-in-your throat; it’s a potentially deadly infection that is extremely preventable.

So what’s going on? Not for one second do we think that there are parents out there who think, “Eh, whooping cough will help my infant build character.” Research suggests that people reject established science when it conflicts with some deeply held value, and/or when accepting the science would cause the person to feel like an outsider or traitor to their community . When it comes to antivaccination, the research shows that parents who don't get their children vaccinated base their decision on anecdotal evidence, and often believe that the “establishment” is exaggerating the benefits and downplaying the risk of vaccination. Once the idea is planted, or the rejection of the science takes hold in a particular community, the problem escalates because any information to the contrary is rejected.

So what can be done to help combat denialism? Education is the obvious answer. Of course, NCSE is focused primarily on defending the teaching of science, and as far as we’re aware, there’s no concerted attempt to undermine the scientific integrity of what’s taught about vaccination in public schools. So NCSE is unlikely to be adding vaccination to its portfolio of evolution and climate change. But it would be remiss of us, as concerned citizens and parents with some expertise in dealing with science denial, not to offer some advice about how to educate ourselves and others.

It’s not as simple as spreading the gospel of science; we also need to help the public become critical consumers of information so they can spot the hallmarks of bad science: cherry picking information, casting doubt on scientists' motives, exaggerating the implications of the science, and claiming that the scientific community is stifling debate. Whether it’s denial of vaccines, climate change, or evolution, the playbook is the same—the trick is to spot the tactics before they lure you in. The people that opt not to vaccinate their children probably have no problem accepting the science that shows that smoking causes cancer, but they fail to recognize that they are falling victim to the same approach used by tobacco companies for decades to encourage smoking.

To successfully change minds, it’s important to catch the denialism before it becomes entrenched. When we encounter someone who questions the science (of vaccines, climate change, or evolution), we must try and understand the roots of their convictions, to engage them with patience and respect. We must ask a lot of questions, find out where they get their information, whom they trust, and what it might take to change their minds. We also must recognize that we are all susceptible to falling into the trap of insulated thinking. Even scientists have biases about how the world works, and they tend to lend more credibility to sources that agree with those biases than those that conflict.

In short, we (however you choose to define “we”) must not play into their (however you choose to define “their”) misconceptions of who we are: elitist, out-of-touch, and close-minded.

These are not easy conversations to have. If you’re the kind of person who thrives on data and analysis, it can be difficult to resist pouring on the facts. However, evidence shows that this approach does not work, and in fact, it can have the opposite of the intended effect, causing deniers to become defensive and retreat. So instead, try to listen. Ask questions. Show concern, not contempt. What’s the worst that could happen? Perhaps you’ll persuade one person to think about science and scientists a little differently. And maybe we get one fewer outbreak of whooping cough.