Climate change denier Mark Steyn is upset. Being upset is, I suppose, an occupational requirement for his brand of punditry, even in Canada. In this case, though, he’s upset that climate scientist Michael Mann is pursuing, so far successfully, a libel suit against Steyn and Steyn’s colleagues. Steyn wrote a column charging Mann with fraud and likening him to convicted child abuser Jerry Sandusky, leaving Mann lots of grounds for a lawsuit. Steyn’s response is to double down on those claims, and to say that Mann is just as bad, because, well…

It’s equally outrageous to call anyone who disagrees with you a “denier,” a slur with a very particular pedigree, and one which would be distressing to any critic of Mann with family who died in the Holocaust.

This is a common charge (here’s the Discovery Institute's version), but it doesn’t hold up. As we at NCSE observe on our page “Why Is It Called Denial?”, the terms “climate change denial” and “climate change denier” are common in the research literature, and even preferred by some prominent deniers.

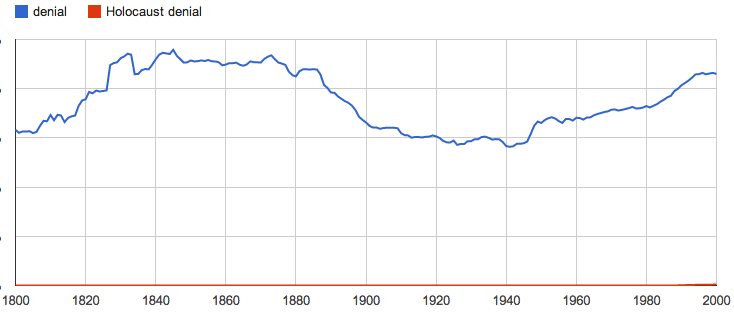

As to the claim that the term “denier” has, in Steyn’s words, “a very particular pedigree,” referring specifically to the Holocaust, we can put that to rest easily enough by looking at how frequently the term “denier” has been used through history. Here’s Google’s record of the word “denial” in English books for the last two centuries (I use “denial” rather than “denier” since the latter word also refers to a coin and a unit of linear mass density used to measure fibers):

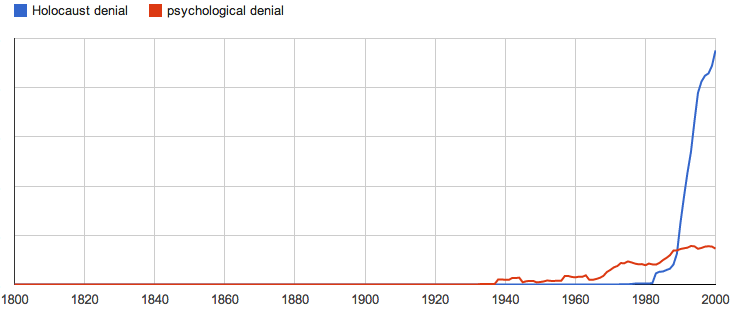

The term “denial” has a long history, and its increased use since the 1950s doesn’t seem at all tied to the idea of Holocaust denial. Indeed, focusing on that phrase alone reveals that it didn’t come into common use until the 1980s:

That makes sense, since the Holocaust denial movement didn’t really take off until the late ‘70s (with the founding of the Institute for Historical Review) and came to prominence in the late ‘80s when the Committee for Open Debate on the Holocaust began trying to place Holocaust-denying advertisements in college newspapers.

The phrase “Holocaust denial” was hardly sui generis in the 1980s. The idea of denial in that sense goes back to Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna. That’s why you see “psychological denial” popping up in the ngram above in the late ‘30s. It picks up again after the ‘60s, when Elisabeth Kübler-Ross used the term to describe the first stage of grieving. By the 1980s, it had even picked up a pithy pop-psych cliche: “Denial’s not just a river in Egypt.” As the Mayo Clinic explains, denial means “not being realistic about something that’s happening in your life—something that might be obvious to those around you.” The Oxford English Dictionary traces the term’s application in psychology to a 1914 translation of Freud’s Psychopathology of Everyday Life—“Certain denials which we encounter in medical practice can probably be ascribed to forgetting.” Freud himself didn’t use the term originally; as Otto Rank complained, “Freud is obliged to refer to special mechanisms, in particular the ‘procedure of making a thing as if it had not happened’—a circumlocution by which he avoids using the simpler and more natural terms proposed by others.” Such as, he added, Verleugnung, i.e., denial.

Steyn is right that the term “denier” has a very particular pedigree; he just misidentifies it. Why should he (and other deniers) be so quick to wrongly charge opponents with misusing the Holocaust to score points? To understand that, we need to turn to another line from the psychological lexicon: projection.